Symphony No. 5 (Tchaikovsky)

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Op. 64 by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky was composed between May and August 1888 and was first performed in Saint Petersburg at the Mariinsky Theatre on November 17 of that year with Tchaikovsky conducting. It is dedicated to Theodor Avé-Lallemant.[1]

Place among Tchaikovsky's later symphonies

[edit]In the first ten years after graduating from the Saint Petersburg Conservatory in 1865 Tchaikovsky completed three symphonies. After that he started five more symphony projects, four of which led to a completed symphony premiered during the composer's lifetime.

| Work | Op. | Composed | Premiered |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symphony No. 4 | 36 | 1877–1878 | 1878 (Moscow) |

| Manfred Symphony | 58 | 1885 | 1886 (Moscow) |

| Symphony No. 5 | 64 | 1888 | 1888 (St Petersburg) |

| Symphony in E-flat | 79 posth. | 1892 | (sketch, not publicly performed during the composer's lifetime) |

| Symphony No. 6 | 74 | 1893 | 1893 (St Petersburg) |

The fifth symphony was composed in 1888, between the Manfred Symphony of 1885 and the sketches for a Symphony in E-flat, which were abandoned in 1892 (apart from recuperating material from its first movement for an Allegro Brillante for piano and orchestra a year later). As for the numbered symphonies, Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 5 was composed between Symphony No. 4, which had been completed ten years earlier, and Symphony No. 6, composed 5 years later, in the year of the composer's death.

Program

[edit]Unlike its two predecessors, Symphony No. 5 has no clear program. On 15 April 1888, about a month before he began composing the symphony, the composer sketched a scenario for its first movement in his notebook, containing "... a complete resignation before fate, which is the same as the inscrutable predestination of fate ..." It is however uncertain how much of this program has been realised in the composition.[2]

Cyclical structure

[edit]Like the Symphony No. 4, No. 5 is a cyclical symphony, with a recurring main theme. Unlike No. 4, however, the theme is heard in all four movements, a feature Tchaikovsky had first used in the Manfred Symphony, which was completed less than three years before No. 5.

Instrumentation

[edit]The work is scored for 3 flutes (3rd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets in A, 2 bassoons, 4 horns in F, 2 trumpets in A, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, and strings.

Structure

[edit]The symphony is in four movements:

The symphony displays an overall tonal trajectory of E minor to E major. The first movement ends in the minor mode, which allows the narrative to continue through the rest of the symphony:

- E minor (1st mvt) → B minor → E minor → D major (2nd mvt) → F♯ major → D major → F♯ minor → V7 (V4

2) of D major → D major → G♯o7 → D major → A major (3rd mvt) → F♯ minor → A major → E major (4th mvt) → E minor → D major → C major → E minor → F♯ major → E minor → E major

The recurring main theme is used as a device to unify the four movements of the symphony. This motto theme, sometimes dubbed "Fate theme",[2] has a funereal character in the first movement, but gradually transforms into a triumphant march, which dominates the final movement.

A typical performance of the symphony lasts somewhat less than 50 minutes.[2]

First movement

[edit]- Themes and Motives

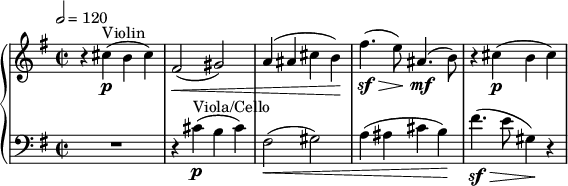

Motto Theme, mm. 1–4:[2]

Primary Theme 1 (PT1), mm. 42–50:[2]

Primary Theme 2 (PT2), mm. 116–128:[2]

Subordinate Theme (ST), mm. 170–182:

Motive X, mm.154–170:

In the exposition of the first movement, the initial tonality (E minor) is relatively unstable. A D major tonality slips in and out E minor as V of the relative major (G major), but not until mm. 128–132 does one hear this as an antagonistic to E minor. The exposition concludes in D major after integrating part of the PT1 into its cadential moment (mm. 194–198). Motive X frames the secondary theme group by preceding the ST and reiterating D major afterwards.

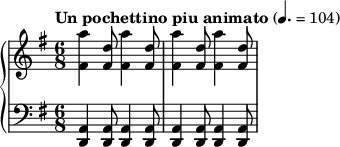

The development consists of four distinct sections. The first section exhibits a sequence based on the PT1 superimposed with motive X. This is accompanied by a bass line that diatonically descends over an octave and a fifth. The second section develops the head motive from PT1. The shifting meter (from 6

8 to 3

4), and diminished sonority (m. 261 for example) adds to growing instability. The third section is a brief allusion to the PT2, interrupted by a fugato based on PT1. Motive X returns strongly and insistently in m. 285, going back and forth between G minor and D minor. This can be interpreted as an effort to re-establish sonority in D. The re-transition to recapitulation is rather abrupt, yet a clever use of common tone modulation can be observed.

The recapitulation of this movement follows the convention of sonata form.

Second movement

[edit]- Themes

The second movement begins with the continuation of the tragic sonority in B minor, as if the movement will be in the minor dominant of the tonic of the symphony. Instead, a common chord modulation leads to a D major theme first introduced by a solo horn.

Theme A1 (1st horn):[2]

Theme A2 (oboe/horn):

Theme B (clarinet in A):[2]

This movement is in a standard ternary form with the A section in D major, the B section alluding to F♯ minor, then a restatement of the A section with different orchestration. Compared to the stable A section, the B section exhibits instability in many ways. For example, the theme begins and remains in V7 of F♯ minor, even though it could be easily resolved to F♯ minor. Moreover, the segmentation of a theme, fugato texture, and rapid shift of hyper meter contributes to the instability of this section.

In this movement, the motto theme appears twice: from mm. 99–103 as a structural dominant preparing the return of the A section, and in the coda (mm. 158–166) in G♯7. One could interpret this as a preparation for I6, but also as a structural leading tone to the next movement (G♯7 → A), especially since the unwinding from the climactic restatement of the motto theme occurs relatively hesitantly and what follows seems to diminish away.[2]

Third movement

[edit]- Themes

Waltz 1:

Waltz 2 (ob 1):

Waltz 3:

Trio:

The third movement is a waltz,[2] with some unusual elements, for example, hemiola and unbalanced phrase structure at the outset of the movement. These elements take over the movement in the trio section, which is a scherzo. The scherzo theme initially played by the first violins can be seen as a superimposition of 4

4 over 3

4. Hemiola is used again as a transitional technique (mm. 97–105). The waltz returns, but with the texture from the scherzo.

The return of the motto theme in the third movement, preceded by a waltz in a major mode, recalls the opening of the symphony,[2] but with a hemiola element:

Fourth movement

[edit]- Themes

Introduction – Motto Theme:[2]

PT1 (violin I):

PT2:

ST:

The exposition of the last movement begins in E minor, whilst the D major sonority seeks to establish itself. Unlike the first movement, there is an early statement in D major, as well as in V7 of D major (mm. 86–90, 106–114). A passage of key oppositions, increasing harmonic rhythm, segmentation, and rapid changes of themes culminates at m. 172 with the re-introduction of the motto theme in C major.[2]

The development is very brief, lasting about 60 measures. In the recapitulation, a new melody is superimposed over the texture, but never returns.

The sixth statement of the motto theme is in E minor, leading to an emphatic Perfect Authentic Cadence (PAC) in B major. Following this, the coda succeeds in reemphasizing the tonic, using different themes and many cadences in the tonic. Some of the themes used here are the motto theme (m. 474), the countermelody to PT1 (m. 474, superimposed onto the motto theme), PT2 (m. 504), and PT1 from the first movement of the symphony.

Critical reaction

[edit]Some critics, including Tchaikovsky himself, have considered the ending insincere or even crude. After the second performance, Tchaikovsky wrote, "I have come to the conclusion that it is a failure". Despite this, the symphony has gone on to become one of the composer's most popular works. The second movement, in particular, is considered to be classic Tchaikovsky: well crafted, colorfully orchestrated, and with a memorable melody for solo horn.

Possibly for its very clear exposition of the idea of "ultimate victory through strife", the Fifth was very popular during World War II, with many new recordings of the work, and many performances during those years. One of the most notable performances was by the Leningrad Radio Orchestra during the Siege of Leningrad. City leaders had ordered the orchestra to continue its performances to keep the spirits high in the city. On the night of October 20, 1941 they played Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 5 at the city's Philharmonic Hall and it was broadcast live to London. As the second movement began, bombs started to fall nearby, but the orchestra continued playing until the final note. Since the war it has remained very popular, but has been somewhat eclipsed in popularity by the Fourth and Sixth Symphonies.

Critical reaction to the work was mixed, with some enthusiasm in Russia. Valerian Bogdanov-Berezovsky wrote, "The Fifth Symphony is the weakest of Tchaikovsky's symphonies, but nevertheless it is a striking work, taking a prominent place not only among the composer's output but among Russian works in general. ... the entire symphony seems to spring from some dark spiritual experience."

On the symphony's first performance in the United States, critical reaction, especially in Boston, was almost unanimously hostile. A reviewer for the Boston Evening Transcript, October 24, 1892, wrote:

Of the Fifth Tchaikovsky Symphony one hardly knows what to say ... In the Finale we have all the untamed fury of the Cossack, whetting itself for deeds of atrocity, against all the sterility of the Russian steppes. The furious peroration sounds like nothing so much as a horde of demons struggling in a torrent of brandy, the music growing drunker and drunker. Pandemonium, delirium tremens, raving, and above all, noise worse confounded!

The reception in New York was little better. A reviewer for the Musical Courier, March 13, 1889, wrote:

In the Tchaikovsky's Fifth Symphony ... one vainly sought for coherency and homogeneousness ... in the last movement, the composer's Calmuck blood got the better of him, and slaughter, dire and bloody, swept across the storm-driven score.

Uses of the symphony

[edit]"Farewell, Amanda", written by Cole Porter for the 1949 Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn film Adam's Rib, draws liberally from the 4th movement of Tchaikovsky's 5th Symphony.[3]

It is suggested by Ian MacDonald that a fragment of the "fate" theme is quoted by Dmitri Shostakovich in his Symphony No. 7 in the "invasion" theme of the first movement.[4][page needed]

Part of the second movement was given English lyrics under the title Moon Love and Love Is All That Matters.[2]

The beginning of Annie's Song by John Denver is almost identical to the first horn theme in the second movement, but it seems this was unintentional and only pointed out to Denver by his producer Milt Okun.[5]

An arrangement of the second movement was used in a prominent 1970s Australian advertisement for Winfield cigarettes.[6]

Notable recordings

[edit]Concertgebouworkest, Willem Mengelberg (1929)

Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra, Yevgeny Mravinsky (Deutsche Gramophone, 1960)

New York Philharmonic, Leonard Bernstein (CBS, 1960)

London Symphony Orchestra, Igor Markevitch (Philips, 1966)

Oslo Philharmonic, Mariss Jansons (Chandos, 1986)

Wiener Philharmoniker, Valery Gergiev (Philips, 1998)

London Philharmonic Orchestra, Vladimir Jurowski (LPO, 2012)

Frankfurt Radio Symphony, Manfred Honeck (YouTube, 2018)

Concertgebouworkest, Semyon Bychkov (YouTube, 2020)

London Philharmonic Orchestra, Mstislav Rostropovich (1977, EMI)

References

[edit]- ^ "Symphony No. 5". Tchaikovsky Research. Retrieved June 21, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Steinberg at SFS website.[dead link]

- ^ "Behind the Song: Leonore No. 1, Farewell Amanda, One Night". Culturedarm.com. 19 October 2014. Retrieved 2020-05-28.

- ^ MacDonald, Ian, The New Shostakovich (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1990). ISBN 1-55553-089-3

- ^ Alfonso, Barry. (2005). Back Home Again (pp. 2–3) [CD Booklet]. New York City: Sony BMG Music Entertainment.[incomplete short citation]

- ^ "Winfield theme [music] / an arrangement by Waldo De Los Rios of Tchaikovsky theme used by Winfield Cigarettes", National Library of Australia.

Sources

[edit]- Review by Bogdanov-Berezovsky, paraphrased from The Symphonies of Brahms and Tschaikowsky in Score, Bonanza Books, New York, 1935.

- Newspaper reviews quoted in Nicolas Slonimsky, The Lexicon of Musical Invective. Seattle, University of Washington Press, 1965. ISBN 0-295-78579-9

- Hans Keller: 'Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky', in Vol. I of 'The Symphony', ed. Robert Simpson (Harmondsworth, 1966).

- The Symphony by Michael Steinberg, Oxford University Press 1995

- Michael Steinberg. "Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 5 in E Minor, Opus 64" Archived 2015-09-06 at the Wayback Machine at San Francisco Symphony website.

Further reading

[edit]- Kraus, Joseph C. (Spring 1991). "Tonal Plan and Narrative Plot in Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 5 in E Minor." Music Theory Spectrum, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 21–47.

- Seibert, Donald C. (1990). "The Tchaikovsky 'Fifth:' a symphony without a programme." The Music Review, vol. 51, no. 1, pp. 36–45.

![\relative c' { \time 6/8 \clef treble \key e \minor \tempo "Allegro con anima" 4. = 104 \partial 8*1 c8( e)[ r16 e e8~] e fis-.( g-.) a( g) fis( e4) c8( g')[ r16 g16 g8~] g[ r16 fis fis8~] fis[ r16 e e8~] e4 }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/f/q/fqw20d5tnsflb4z4i2z2ua5hlztz0hv/fqw20d5t.png)

![\relative c' { \clef treble \time 12/8 \key d \major \tempo "Con moto" 4. = 60 << { \stemUp fis'4.^"oboe" ais,4( dis8) cis2. | fis4. ais,4( dis8) cis2. | \times 3/2 { cis8--[ dis--] } \times 3/2 { eis--[ fis--] } \times 3/2 { ais--([ gis--)] } \times 3/2 { fisis--[ gis--] } | b4.( ais) s2. | s } \\ { \stemDown s2. gis,4._"horn" dis4( eis8) | fis4.~ fis8 s s gis4. dis4( eis8) | fis4.~ fis8 s s s2. | \times 3/2 { cis8--[ dis--] } \times 3/2 { eis--[ fis--] } \times 3/2 { ais--([ gis--)] } \times 3/2 { g--[ gis--] } | b4.( ais) } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/p/z/pzyh5s2narpmsfdahjme5p899rrib6j/pzyh5s2n.png)

![\relative c'' { \clef treble \time 3/4 \key a \major \tempo "Allegro moderato" 4 = 138 cis4.^"Violin I" b8( a gis) | fis4( e2) | fis4. gis8( a fis) | b2. | dis,4. e8( fis gis) | b4( a2) | cis,4. dis8( e fis) | a4. gis8( fis e | eis->[ fis)] }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/t/e/teelpe04r24rgz4d5cndagxequg3sbc/teelpe04.png)

![\relative c' { \clef bass \time 3/4 \key a \major \tempo 4 = 138 \partial 8*3 b8(^"Bassoon" d cis) | ais4.-> b8( d cis) | ais4.-> b8( d cis) | ais4.-> b8( cis d) | fis( e4) a4( b,8~ | b gis'4 a,) fis'8~( | fis g,4 e' fis,8~ | fis) d'4( f, cis'8~ cis[ b e,)] }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/7/n/7n37eooykspx3r58slnh781gpdhd1ni/7n37eooy.png)

![\relative c'' { \clef treble \time 3/4 \key a \major \tempo 4 = 138 \partial 16*4 fis16-.^"Violin I" gis-. fis-. gis-. | a-. gis-. fis-. e-. d-. e-. d-. e-. fis-. e-. d-. cis-. | b-. cis-. b-. cis-. d-. cis-. b-. a-. gis-. a-. gis-. a-. | b-. a-. gis-. fis-. eis-. fis-. gis-. a-. b-. cis-. d-. b-. | cis8->([ fis,)] }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/f/3/f34zn873awpera0y1if3rrppr0bdgb2/f34zn873.png)