Christian Church

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

In ecclesiology, the Christian Church is what different Christian denominations conceive of as being the true body of Christians or the original institution established by Jesus Christ.[1][2][3] "Christian Church" has also been used in academia as a synonym for Christianity, despite the fact that it is composed of multiple churches or denominations, many of which hold a doctrinal claim of being the one true church to the exclusion of the others.[4][5][6]

For many Protestant Christians, the Christian Church has two components: the church visible, institutions in which "the Word of God purely preached and listened to, and the sacraments administered according to Christ's institution", as well as the church invisible—all "who are truly saved" (with these beings members of the visible church).[7][2][8] In this understanding of the invisible church, "Christian Church" (or catholic Church) does not refer to a particular Christian denomination, but includes all individuals who have been saved.[2] The branch theory, which is maintained by some Anglicans, holds that those Churches that have preserved apostolic succession are part of the true Church.[9] This is in contrast to the one true church applied to a specific concrete Christian institution, a Christian ecclesiological position maintained by the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Oriental Orthodox churches, Assyrian Church of the East, and the Ancient Church of the East.[1][10][3]

Most English translations of the New Testament generally use the word church as a translation of the Ancient Greek ἐκκλησία (romanized ecclesia), found in the original Greek texts, which generally meant an "assembly" or "congregation".[11] This term appears in two verses of the Gospel of Matthew, 24 verses of the Acts of the Apostles, 58 verses of the Pauline epistles (including the earliest instances of its use in relation to a Christian body), two verses of the Letter to the Hebrews, one verse of the Epistle of James, three verses of the Third Epistle of John, and 19 verses of the Book of Revelation. In total, ἐκκλησία appears 114 times in the New Testament, although not every instance is a technical reference to the church.[12] As such it is used for local communities as well as in a universal sense to mean all believers.[13] The earliest recorded use of the term Christianity (Greek: Χριστιανισμός) was by Ignatius of Antioch, in around 100 AD.[14]

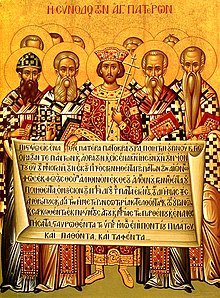

The Four Marks of the Church first expressed in the Nicene Creed (381) are that the Church is one, holy, catholic (universal), and apostolic (originating from the apostles).[15]

Etymology

[edit]The Greek word ekklēsia, literally "called out" or "called forth" and commonly used to indicate a group of individuals called to gather for some function, in particular an assembly of the citizens of a city, as in Acts 19:32–41, is the New Testament term referring to the Christian Church (either a particular local group or the whole body of the faithful). In the Septuagint, the Greek word "ἐκκλησία" is used to translate the Hebrew "קהל" (qahal). Most Romance and Celtic languages use derivations of this word, either inherited or borrowed from the Latin form ecclesia.

The English language word "church" is from the Old English word cirice or Circe, derived from West Germanic *kirika, which in turn comes from the Greek κυριακή kuriakē, meaning "of the Lord" (possessive form of κύριος kurios "ruler" or "lord"). Kuriakē in the sense of "church" is most likely a shortening of κυριακὴ οἰκία kuriakē oikia ("house of the Lord") or ἐκκλησία κυριακή ekklēsia kuriakē ("congregation of the Lord").[16] Christian churches were sometimes called κυριακόν kuriakon (adjective meaning "of the Lord") in Greek starting in the 4th century, but ekklēsia and βασιλική basilikē were more common.[17]

The word is one of many direct Greek-to-Germanic loans of Christian terminology, via the Goths. The Slavic terms for "church" (Old Church Slavonic црькꙑ [crĭky], Bulgarian църква [carkva], Russian церковь [cerkov'], Slovenian cerkev) are via the Old High German cognate chirihha.[citation needed]

History

[edit]

The Christian Church originated in Roman Judea in the first century AD/CE, founded on the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth, who first gathered disciples. Those disciples later became known as "Christians"; according to Scripture, Jesus commanded them to spread his teachings to all the world. For most Christians, the holiday of Pentecost (an event that occurred after Jesus' ascension to Heaven) represents the birthday of the Church,[18][19][20] signified by the descent of the Holy Spirit on gathered disciples.[21][22]

Springing out of Second Temple Judaism, from Christianity's earliest days, Christians accepted non-Jews (Gentiles) without requiring full adoption of Jewish customs (such as circumcision).[23][24] The parallels in the Jewish faith are the Proselytes, Godfearers, and Noahide Law; see also Biblical law in Christianity. Some think that conflict with Jewish religious authorities quickly led to the expulsion of Christians from the synagogues in Jerusalem.[25]

The Church gradually spread throughout the Roman Empire and beyond, gaining major establishments in cities such as Jerusalem, Antioch, and Edessa.[26][27][28] The Roman authorities persecuted it because Christians refused to make sacrifice to the Roman gods, and challenged the imperial cult.[29] The Church was legalized in the Roman empire, and then promoted by Emperors Constantine I and Theodosius I in the 4th century as the State Church of the Roman Empire.

Already in the 2nd century, Christians denounced teachings that they saw as heresies, especially Gnosticism but also Montanism. Ignatius of Antioch at the beginning of that century and Irenaeus at the end saw union with the bishops as the test of correct Christian faith. After legalization of the Church in the 4th century, the debate between Arianism and Trinitarianism, with the emperors favouring now one side now the other, was a major controversy.[30][31]

Use by early Christians

[edit]

In using the word ἐκκλησία (ekklēsia), early Christians were employing a term that, while it designated the assembly of a Greek city-state, in which only citizens could participate, was traditionally used by Greek-speaking Jews to speak of Israel, the people of God,[32] and that appeared in the Septuagint in the sense of an assembly gathered for religious reasons, often for a liturgy; in that translation ἐκκλησία stood for the Hebrew word קהל (qahal), which however it also rendered as συναγωγή (synagōgē, "synagogue"), the two Greek words being largely synonymous until Christians distinguished them more clearly.[33]

The term ἐκκλησία appears in only two verses of the Gospels, in both cases in the Gospel of Matthew.[32] When Jesus says to Simon Peter, "You are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church",[34] the church is the community instituted by Christ, but in the other passage the church is the local community to which one belongs: "If he refuses to listen to them, tell it to the church."[35]

The term is used much more frequently in other parts of the New Testament, designating, as in the Gospel of Matthew, either an individual local community or all of them collectively. Even passages that do not use the term ἐκκλησία may refer to the church with other expressions, as in the first 14 chapters of the Epistle to the Romans, in which ἐκκλησία is totally absent but which repeatedly uses the cognate word κλήτοι (klētoi, "called").[36] The church may be referred to also through images traditionally employed in the Bible to speak of the people of God, such as the image of the vineyard used particularly in the Gospel of John.[33]

The New Testament never uses the adjectives "catholic" or "universal" with reference to the Christian Church, but does indicate that the local communities are one church, collectively, that Christians must always seek to be in concord, as the Congregation of God, that the Gospel must extend to the ends of the earth and to all nations, that the church is open to all peoples and must not be divided, etc.[32]

The first recorded application of "catholic" or "universal" to the church is by Ignatius of Antioch in about 107 in his Epistle to the Smyrnaeans, chapter VIII: "Wherever the bishop appears, there let the people be; as wherever Jesus Christ is, there is the Catholic Church."[37]

Christianity as Roman state religion

[edit]

On February 27, 380, the Roman Empire officially adopted the Nicene version of Christianity as its state religion. Prior to this date, Constantius II (337–361) and Valens (364–378) had personally favored Arian or Semi-Arian forms of Christianity, but Valens' successor Theodosius I supported the more Athanasian or Trinitarian doctrine as expounded in the Nicene Creed from the 1st Council of Nicaea.j

On this date, Theodosius I decreed that only the followers of Trinitarian Christianity were entitled to be referred to as Catholic Christians, while all others were to be considered to be heretics, which was considered illegal.[38] In 385, this new legal situation resulted, in the first case of many to come, in the capital punishment of a heretic, namely Priscillian, condemned to death, with several of his followers, by a civil tribunal for the crime of magic.[39] In the centuries of state-sponsored Christianity that followed, pagans and heretical Christians were routinely persecuted by the Empire and the many kingdoms and countries that later occupied its place,[40] but some Germanic tribes remained Arian well into the Middle Ages[41] (see also Christendom).

The Church within the Roman Empire was organized under metropolitan sees, with five rising to particular prominence and forming the basis for the Pentarchy proposed by Justinian I. Of these five, one was in the West (Rome) and the rest in the East (Constantinople, Jerusalem, Antioch, and Alexandria).[42]

Even after the split of the Roman Empire the Church remained a relatively united institution (apart from Oriental Orthodoxy and some other groups which separated from the rest of the state-sanctioned Church earlier). The Church came to be a central and defining institution of the Empire, especially in the East or Byzantine Empire, where Constantinople came to be seen as the center of the Christian world, owing in great part to its economic and political power.[44][45]

Once the Western Empire fell to Germanic incursions in the 5th century, the (Roman) Church became for centuries the primary link to Roman civilization for medieval Western Europe and an important channel of influence in the West for the Eastern Roman, or Byzantine, emperors. While, in the West, the so-called orthodox Church competed against the Arian Christian and pagan faiths of the Germanic rulers and spread outside what had been the Empire to Ireland, Germany, Scandinavia, and the western Slavs, in the East Christianity spread to the Slavs in what is now Russia, south-central and eastern Europe.[46]

Starting in the 7th century, the Islamic Caliphates rose and gradually began to conquer larger and larger areas of the Christian world.[46] Excepting North Africa and most of Spain, northern and western Europe escaped largely unscathed by Islamic expansion, in great part because richer Constantinople and its empire acted as a magnet for the onslaught.[47] The challenge presented by the Muslims would help to solidify the religious identity of eastern Christians even as it gradually weakened the Eastern Empire.[48] Even in the Muslim World, the Church survived (e.g., the modern Copts, Maronites, and others) albeit at times with great difficulty.[49][50]

Great Schism of 1054

[edit]Although there had long been frictions between the Bishop of Rome (i.e., the patriarch of the Catholic Church proper) and the eastern patriarchs within the Byzantine Empire, Rome's changing allegiance from Constantinople to the Frankish king Charlemagne set the Church on a course towards separation. The political and theological divisions would grow until Rome and the East excommunicated each other in the 11th century, ultimately leading to the division of the Church into the Western (Catholic) and Eastern (Orthodox) churches.[46] In 1448, not long before the Byzantine Empire collapsed, the Russian Orthodox Church gained independence from the Patriarch of Constantinople.[citation needed]

As a result of the redevelopment of Western Europe, and the gradual fall of the Eastern Roman Empire to the Arabs and Turks (helped by warfare against Eastern Christians), the final Fall of Constantinople in 1453 resulted in Eastern scholars fleeing to the West bringing ancient manuscripts, which was a factor in the beginning of the period of the Western Renaissance there. Rome was seen by the Western Church as Christianity's heartland.[51] Some Eastern churches even broke with Eastern Orthodoxy and entered into communion with Rome (the "Uniate" Eastern Catholic Churches).

Protestant Reformation

[edit]The changes brought on by the Renaissance eventually led to the Protestant Reformation during which the Protestant Lutheran and the Reformed followers of Calvin, Hus, Zwingli, Melancthon, Knox, and others split from the Catholic Church. At this time, a series of non-theological disputes also led to the English Reformation which led to the independence of the Church of England. Then, during the Age of Exploration and the Age of Imperialism, Western Europe spread the Catholic Church and the Protestant churches around the world, especially in the Americas.[52][53] These developments in turn have led to Christianity being the largest religion in the world today.[54]

Catholic tradition

[edit]The Catholic Church teaches in its doctrine that it is the original church founded by Christ on the Apostles in the 1st century AD.

The encyclical of Pope Pius IX, Singulari Quidem, states: "There is only one true, holy, Catholic Church, which is the Apostolic Roman Church. There is only one See founded on Peter by the word of the Lord [...] Outside of the Church, no one can hope for life or salvation unless he is excused through ignorance beyond his control."

The papal encyclical Mystici corporis (Pope Pius XII, 1943), expresses the dogmatic ecclesiology of the Catholic Church thus: "If we would define and describe this true Church of Jesus Christ—which is the One, Holy, Catholic, Apostolic, Roman Church–we shall find no expression more noble, more sublime, or more divine, than the phrase which calls it 'the Mystical Body of Jesus Christ'." The Second Vatican Council's dogmatic constitution, Lumen gentium (1964), further declares that "the one Church of Christ which in the Creed is professed as one, holy, catholic and apostolic, [...] constituted and organized in the world as a society, subsists in the Catholic Church, which is governed by the successor of Peter and by the Bishops in communion with him".[55][56]

A 2007 declaration of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith clarified that, in this passage, "'subsistence' means this perduring, historical continuity and the permanence of all the elements instituted by Christ in the Catholic Church, in which the Church of Christ is concretely found on this earth", and acknowledged that grace can be operative within religious communities separated from the Catholic Church due to some "elements of sanctification and truth" within them, but also added "Nevertheless, the word 'subsists' can only be attributed to the Catholic Church alone precisely because it refers to the mark of unity that we profess in the symbols of the faith (I believe... in the 'one' Church); and this 'one' Church subsists in the Catholic Church."[57]

The Catholic Church teaches that only corporate bodies of Christians led by bishops with valid holy orders can be recognized as "churches" in the proper sense. In Catholic documents, communities without such bishops are formally called ecclesial communities.

Eastern Orthodox tradition

[edit]The Eastern Orthodox Church claims to be the original Christian Church. The Eastern Orthodox Church bases its claim primarily on its assertion that it holds to traditions and beliefs of the original Christian Church. It also claims that four out of the five sees of the Pentarchy (excluding Rome) are still a part of it.

Oriental Orthodox tradition

[edit]The Oriental Orthodox Churches claims to be the original Christian Church. The Oriental Orthodox churches' bases their claim primarily on its assertion that it holds to traditions and beliefs of the original Christian Church. They never adopted the theory of the Nature of God, which was formulated later than the break that followed the Council of Chalcedon.

Lutheran tradition

[edit]

The Lutheran churches traditionally hold that their tradition represents the true visible Church.[59] The Augsburg Confession found within the Book of Concord, a compendium of belief of the Lutheran Churches, teaches that "the faith as confessed by Luther and his followers is nothing new, but the true catholic faith, and that their churches represent the true catholic or universal church".[60] When the Lutherans presented the Augsburg Confession to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor in 1530, they believe to have "showed that each article of faith and practice was true first of all to Holy Scripture, and then also to the teaching of the church fathers and the councils".[60]

Nevertheless, the Lutheran churches teach that "there are indeed true Christians in other churches" as "other denominations also preach the Word of God, though mixed with error"; since the proclamation of the Word of God bears fruit, Lutheran theology accepts the appellation "Church" for other Christian denominations.[59]

Anglican tradition

[edit]Anglicans generally understand their tradition as a branch of the historical "Catholic Church" and as a via media ("middle way") between traditions, often Lutheranism and Reformed Christianity, or Roman Catholicism and Reformed Christianity.[61]

Reformed tradition

[edit]Reformed theology defines the Church as being invisible and visible—the former includes the entire communion of saints and the latter is the "institution that God provides as an agency for God's saving, justifying, and sustaining activity", which John Calvin referred to as "our mother".[62] The Reformed confessions of faith emphasize "the pure teaching of the gospel (pura doctrina evangelii) and the right administration of the sacraments (recta administratio sacramentorum)" as "the two most necessary signs of the true visible church".[63]

Methodist tradition

[edit]

Methodists affirm belief in "the one true Church, Apostolic and Universal", viewing their churches as constituting a "privileged branch of this true church".[65][66] With regard to the position of Methodism within Christendom, the founder of the movement "John Wesley once noted that what God had achieved in the development of Methodism was no mere human endeavor but the work of God. As such it would be preserved by God so long as history remained."[67] Calling it "the grand depositum" of the Methodist faith, Wesley specifically taught that the propagation of the doctrine of entire sanctification was the reason that God raised up the Methodists in the world.[68][64]

Baptist tradition

[edit]Many Baptists, who uphold the doctrine of Baptist successionism (also known as Landmarkism), "argue that their history can be traced across the centuries to New Testament times" and "claim that Baptists have represented the true church" that "has been, present in every period of history".[69][70] Walter B. Shurden, the founding executive director of the Center for Baptist Studies at Mercer University, writes that the theology of Landmarkism, which he states is integral of the history of the Southern Baptist Convention, upholds the ideas that "Only Baptist churches can trace their lineage in uninterrupted fashion back to the New Testament, and only Baptist churches therefore are true churches."[71] In addition Shurden writes that Baptists who uphold successionism believe that "only a true church-that is, a Baptist church-can legitimately celebrate the ordinances of baptism and the Lord's Supper. Any celebration of these ordinances by non-Baptists is invalid."[70][71]

Other Baptists do not adhere to Landmarkism and thus hold a broader understanding of what constitutes the true Christian Church, e.g. the American Baptist Churches (which are maintain ecumenical relations with other Churches).[72]

Pentecostal tradition

[edit]In Pentecostalism, "ecclesiology as seen through his concept of networks, where the Holy Spirit creates an openness in mission which allows for coordinated effort towards church planting and growth."[73]

Divisions and controversies

[edit]Today there is a wide diversity of Christian groups, with a variety of different doctrines and traditions. These controversies between the various branches of Christianity naturally include significant differences in their respective ecclesiologies.

Christian denominations

[edit]"Denomination" is a generic term for a distinct Christian body identified by traits such as a common name, structure, leadership, or doctrine. Individual bodies, however, may use alternative terms to describe themselves, such as "church" or "fellowship". Divisions between one group and another are defined by doctrine and church authority; issues such as the nature of Jesus, the authority of apostolic succession, eschatology, and papal primacy often separate one denomination from another. Groups of denominations often sharing broadly similar beliefs, practices, and historical ties are known as branches of Christianity.

Individual Christian denominations vary widely in the degree to which they recognize one another. Several claim to be the direct and sole authentic successor the church founded by Jesus Christ in the 1st century AD. Others, however, believe in denominationalism, where some or all Christian denominations are legitimate churches of the same religion regardless of their distinguishing labels, beliefs, and practices. Because of this concept, some Christian bodies reject the term "denomination" to describe themselves, to avoid implying equivalency with other churches or denominations.[citation needed]

The Catholic Church and Eastern Orthodox Church believe that the term one in the Nicene Creed describes and prescribes a visible institutional and doctrinal unity, not only geographically throughout the world, but also historically throughout history. They see unity as one of the four marks that the Creed attributes to the genuine Church, and the essence of a mark is to be visible. A church whose identity and belief varied from country to country and from age to age would not be "one" in their estimation. As such they see themselves not as a denomination, but as pre-denominational; not as one of many faith communities, but the original and sole true Church.[citation needed]

Many Baptist and Congregationalist theologians accept the local sense as the only valid application of the term church. They strongly reject the notion of a universal (catholic) church. These denominations argue that all uses of the Greek word ekklesia in the New Testament are speaking of either a particular local group or of the notion of "church" in the abstract, and never of a single, worldwide Church.[74][75]

Many Anglicans, Lutherans, Old Catholics, and Independent Catholics view unity as a mark of catholicity, but see the institutional unity of the Catholic Church as manifested in the shared apostolic succession of their episcopacies, rather than a shared episcopal hierarchy or rites.[citation needed]

Reformed Christians hold that every person justified by faith in the Gospel committed to the Apostles is a member of "One, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church". From this perspective, the real unity and holiness of the whole church established through the Apostles is yet to be revealed; and meanwhile, the extent and peace of the church on earth is imperfectly realized in a visible way.[citation needed]

The Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod declares that the Christian Church, properly speaking, consists only of those who have faith in the gospel (i.e., the forgiveness of sins which Christ gained for all people), even if they are in church bodies that teach error, but excluding those who do not have such faith, even if they belong to a church or hold a teaching office in it.[76]

World Christianity

[edit]A number of historians have noted a twentieth-century "global shift" in Christianity, from a religion largely found in Europe and the Americas to one which is found in the global south.[77][78][79] Described as "World Christianity" or "Global Christianity", this term attempts to convey the global nature of the Christian religion. However, the term often focuses on "non-Western Christianity" which "comprises (usually the exotic) instances of Christian faith in 'the global South', in Asia, Africa and Latin America."[80] It also includes indigenous or diasporic forms in Western Europe and North America.[81]

See also

[edit]- Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral

- Church architecture

- Church attendance

- Churching of women

- Ecumenism

- Evangelical Catholic

- Germanic Christianity

- Great Church

- High church and Low church

- Inculturation

- Kingdom of God

- List of Christian denominations

- List of Christian denominations by number of members

- List of popes

- Missiology

- Priesthood of all believers

- Restoration Movement

- Role of the Christian Church in civilization

- Unam sanctam

References

[edit]- ^ a b "The Original Christian Church". Orthodox Church in America. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Weaver, Jonathan (1900). Christian Theology: A Concise and Practical View of the Cardinal Doctrines and Institutions of Christianity. United Brethren Publishing House. p. 245.

There are distinctions between the general invisible church and the general visible church, which it is not necessary to carry out to the last analysis. In a sense, they are both visible. All who are members of the general invisible church are members of the general visible church. But all who are members of the general visible church are not members of the general invisible church. A clear and distinct difference between the visible and invisible church may be stated thus: (1) The general invisible church includes all out of every kindred and tongue and people and nation who are truly saved. No one denomination has in its communion all who belong to the invisible church. (2) The visible church includes all who are recognized as members of a Christian church. No one denomination can justly claim to be the general visible church.

- ^ a b "What do Catholics believe?". Roman Catholic Diocese of Lansing. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

We are the original Christian Church, which began when Jesus himself when he said to the Apostle Peter, "You are the rock on which I will build my church. The gates of hell will not prevail against it." Every pope since then has been part of an unbroken line of succession since Peter, the first pope.

- ^ "Eastern Orthodox Church". BBC. 11 June 2008. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

The doctrine of the Christian Church was established over the centuries at Councils dating from as early as 325CE where the leaders from all the Christian communities were represented.

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D. (29 May 2018). "Inside the Conversion Tactics of the Early Christian Church". History. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

And yet, within three centuries, the Christian church could count some 3 million adherents.

- ^ F. L. Cross; Elizabeth A. Livingstone, eds. (1997). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-211655-X. OCLC 38435185.

- ^ McGrath, Alister E. (4 August 2016). Christian Theology: An Introduction. John Wiley & Sons. p. 362. ISBN 978-1-118-87443-1.

- ^ Schaff, Philip (1910). History of the Christian Church. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 524.

- ^ Kinsman, Frederick Joseph (1924). Americanism and Catholicism. Longman. p. 203.

The one most talked about is the "Branch Theory," which assumes that the basis of unity is a valid priesthood. Given the priesthood, it is held that valid Sacraments unite in spite of schisms. Those who hold it assume that the Church is composed of Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, eastern heretics possessing undisputed Orders, and Old Catholics, Anglicans, Swedish Lutherans, Moravians, and any others who might be able to demonstrate that they had perpetuated a valid hierarchy. This is chiefly identified with High Church Anglicans and represents the survival of a seventeenth century contention against Puritans, that Anglicans were not to be classed with Continental Protestants.

- ^ "The Church". Catholic Encyclopedia. 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

It would appear, then, indisputable that in the earliest years of the Christian Church ecclesiastical functions were in a large measure fulfilled by men who had been specially endowed for this purpose with "charismata" of the Holy Spirit, and that as long as these gifts endured, the local ministry occupied a position of less importance and influence.

- ^ Entry for Strong's #1577 - ἐκκλησία - StudyLight.org. Bible Lexicons - Old / New Testament Greek Lexical Dictionary. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ "Ekklesia: A Word Study". Acu.edu. Archived from the original on 3 September 2006. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

- ^ McKim, Donald K., Westminster Dictionary of Theological Terms, Westminster John Knox Press, 1996

- ^ Elwell & Comfort 2001, pp. 266, 828.

- ^ Louis Berkhof, Systematic Theology (London: Banner of Truth, 1949), 572.

- ^ Harper, Douglas (2001). "church". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 18 January 2008.

O.E. cirice "church," from W.Gmc. *kirika, from Gk. kyriake (oikia) "Lord's (house)," from kyrios "ruler, lord."

- ^ Harper, Douglas (2001). "church". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 18 January 2008.

Gk. kyriakon (adj.) "of the Lord" was used of houses of Christian worship since c. 300, especially in the East, though it was less common in this sense than ekklesia or basilike.

- ^ "Pentecost | Christianity". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ^ "Religions - Christianity: Pentecost". bbc.co.uk. British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ^ Milavec, Aaron (2007). Salvation is from the Jews (John 4:22): Saving Grace in Judaism and Messianic Hope in Christianity. Liturgical Press. p. 90. ISBN 9780814659892. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ^ Acts 2

- ^ "Pentecost (Whitsunday)". Catholic Encyclopedia. Accessed on 4 November 2016.

- ^ Acts 10–15

- ^ "Church as an Institution", Dictionary of the History of Ideas, University of Virginia Library [1] Archived 2006-10-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ An Overview of Christian History, Catholic Resources for Bible, Liturgy, and More [2]

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Donald H. Frew, Harran: Last Refuge of Classical Paganism Colorado State University Pueblo "The Virtual Pomegranate". Archived from the original on 26 August 2004. Retrieved 19 May 2007.

- ^ From Jesus to Christ: Maps, Archaeology, and Sources: Chronology, PBS, retrieved May 19, 2007 [3]

- ^ Sophie Lunn-Rockliffe, Christianity and the Roman Empire: Reasons for persecution, Ancient History: Romans, BBC Home, retrieved May 10, 2007 [4] Archived 2009-08-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Michael DiMaio, Jr., Robert Frakes, Constantius II (337-361 A.D.), De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and their Families [5]

- ^ Michael Hines, Constantine and the Christian State, Church History for the Masses [6]

- ^ a b c François Louvel, "Naissance d'un vocabulaire chrétien" in Les Pères Apostoliques (Paris, Cerf, 2006 ISBN 978-2-204-06872-7), pp. 517-518

- ^ a b Xavier Léon-Dufour (editor), Vocabulaire de théologie biblique (Paris, Cerf, 1981 ISBN 2-204-01720-5), pp. 323-335.

- ^ Matthew 16:18

- ^ Matthew 18:17

- ^ Julienne Côté, Cent mots-clés de la théologie de Paul (ISBN 2-204-06446-7), pp. 157ff

- ^ "St. Ignatius of Antioch to the Smyrnaeans (Roberts-Donaldson translation)". www.earlychristianwritings.com.

- ^ Halsall, Paul (June 1997). "Theodosian Code XVI.i.2". Medieval Sourcebook: Banning of Other Religions. Fordham University. Archived from the original on 27 February 2007. Retrieved 23 November 2006.

- ^ Healy, Patrick (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Ramsay MacMullen, Christianity and Paganism in the Fourth to Eighth Centuries, Yale University Press, September 23, 1997

- ^ Christianity Missions and monasticism, Encyclopædia Britannica Online [7]

- ^ Deno Geanakoplos, A short history of the ecumenical patriarchate of Constantinople, Archons of the Ecumenical Patriarch, retrieved May 20, 2007 [8]

- ^ Moosa, Matti (28 April 2012). "The Christians Under Turkish Rule".

- ^ MSN Encarta: Orthodox Church, retrieved May 12, 2007. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009.

- ^ Arias of Study: Western Art, Department of Art History, University of Wisconsin, retrieved May 17, 2007 [9]

- ^ a b c CHRISTIANITY IN HISTORY, Dictionary of the History of Ideas, University of Virginia Library [10] Archived 2006-09-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Byzantine Empire, byzantinos.com". Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 24 May 2007.

- '^ BYZANTINE ICONOCLASM AND POLITICAL EARTHQUAKE OF ARAB CONQUESTS – AN EMOTIONAL 'GUST, This Century's Review, retrieved May 24, 2007 [11]

- ^ The History of the Copts, California Academy of Sciences "Coptic History". Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 28 October 2007., retrieved May 24, 2007

- ^ History of the Maronite Patriarchate, Opus Libani, retrieved May 24, 2007 "History of the Maronite Patriarchate". Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 28 October 2007.

- ^ Aristeides Papadakis, John Meyendorff, The Christian East and the Rise of the Papacy: The Church 1071-1453 A.D., St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, August 1994, ISBN 0-88141-057-8, ISBN 978-0-88141-057-0

- ^ Christianity and world religions, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ South America:Religion, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Major Religions of the World Ranked by Number of Adherents, Adherents.com [12]

- ^ Lumen gentium Archived September 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, 8

- ^ In The Catholicity of the Church, p. 132, Avery Dulles noted that this document avoided explicitly calling the Church the "Roman" Catholic Church, replacing this term with the equivalent "which is governed by the successor of Peter and by the Bishops in communion with him" and giving in a footnote a reference to two earlier documents in which the word "Roman" is used explicitly.

- ^ Responses to Some Questions Regarding Certain Aspects of the Doctrine on the Church Archived August 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ See Augsburg Confession, Article 7, Of the Church

- ^ a b Frey, H. (1918). "Is One Church as Good as Another?". The Lutheran Witness. Vol. 37. pp. 82–83.

- ^ a b Ludwig, Alan (12 September 2016). "Luther's Catholic Reformation". The Lutheran Witness.

When the Lutherans presented the Augsburg Confession before Emperor Charles V in 1530, they carefully showed that each article of faith and practice was true first of all to Holy Scripture, and then also to the teaching of the church fathers and the councils and even the canon law of the Church of Rome. They boldly claim, "This is about the Sum of our Doctrine, in which, as can be seen, there is nothing that varies from the Scriptures, or from the Church Catholic, or from the Church of Rome as known from its writers" (AC XXI Conclusion 1). The underlying thesis of the Augsburg Confession is that the faith as confessed by Luther and his followers is nothing new, but the true catholic faith, and that their churches represent the true catholic or universal church. In fact, it is actually the Church of Rome that has departed from the ancient faith and practice of the catholic church (see AC XXIII 13, XXVIII 72 and other places).

- ^ Anglican and Episcopal History. Historical Society of the Episcopal Church. 2003. p. 15.

Others had made similar observations, Patrick McGrath commenting that the Church of England was not a middle way between Roman Catholic and Protestant, but "between different forms of Protestantism," and William Monter describing the Church of England as "a unique style of Protestantism, a via media between the Reformed and Lutheran traditions." MacCulloch has described Cranmer as seeking a middle way between Zurich and Wittenberg but elsewhere remarks that the Church of England was "nearer Zurich and Geneva than Wittenberg.

- ^ McKim, Donald K. (1 January 2001). The Westminster Handbook to Reformed Theology. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 34. ISBN 9780664224301.

- ^ Adhinarta, Yuzo (14 June 2012). The Doctrine of the Holy Spirit in the Major Reformed Confessions and Catechisms of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. Langham Monographs. p. 83. ISBN 9781907713286.

- ^ a b Gibson, James. "Wesleyan Heritage Series: Entire Sanctification". South Georgia Confessing Association. Archived from the original on 29 May 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- ^ Newton, William F. (1863). The Magazine of the Wesleyan Methodist Church. J. Fry & Company. p. 673.

- ^ Bloom, Linda (20 July 2007). "Vatican stance "nothing new" say church leader". The United Methodist Church. Archived from the original on 31 May 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ^ William J. Abraham (25 August 2016). "The Birth Pangs of United Methodism as a Unique, Global, Orthodox Denomination". Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ Davies, Rupert E.; George, A. Raymond; Rupp, Gordon (14 June 2017). A History of the Methodist Church in Great Britain, Volume Three. Wipf & Stock Publishers. p. 225. ISBN 9781532630507.

- ^ McGoldrick, James Edward (1 January 1994). Baptist Successionism: A Crucial Question in Baptist History. Scarecrow Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 9780810836815.

Although the two most popular textbooks used in America to teach Baptist history cite Holland and England early in the seventeenth century as the birthplace of the Baptist churches, many Baptists object vehemently and argue that their history can be traced across the centuries to New Testament times. Some Baptists deny categorically that they are Protestants and that the history of their churches is related to the success of the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century. Those who reject the Protestant character and Reformation origins of the Baptists usually maintain a view of church history sometimes called "Baptist successionism" and claim that Baptists have represented the true church, which must be, and has been, present in every period of history. The popularity of the successionist view has been enhanced enormously by a booklet entitled The Trail of Blood, of which thousands of copies have been distributed since it was published in 1931.

- ^ a b Johnson, Robert E. (13 September 2010). A Global Introduction to Baptist Churches. Cambridge University Press. p. 148. ISBN 9781139788984.

One was its belief that the Baptist Church was the only true church. Because only the Baptist Church was an authentically biblical church, all other so-called churches were merely human societies. This mean that only ordinances performed by this true church were valid. All other rites were simply rituals performed by leaders of religious societies. The Lord's Supper could correctly be administered only to members of the local congregation (closed communion). Pastors of other denominations could not be true pastors because their churches were not true churches.

- ^ a b Shurden, Walter B. (1993). The Struggle for the Soul of the SBC: Moderate Responses to the Fundamentalist Movement. Mercer University Press. p. 103. ISBN 9780865544246.

Also, and perhaps more important for this study, The Trail of Blood should be remembered because it was one of the principal documents to support Landmarkism. No historical or doctrinal aberration, I believe, affected Southern Baptist thinking more during the nineteenth century-and still shapes Southern Baptist ecclesiology, especially in the Southwest-than that of Landmarkism. What were the teachings of J.R. Graves, J.M. Pendleton, A.C. Dayton-a dentist converted from Presbyterianism to Baptist Landmarkism-and J.M. Carroll? Briefly, proponents of Landmarkism insisted (1) There is no such entity as the "invisible church" or the "Church Universal." There are only local churches. (2) Only Baptist churches bear the marks of the true New Testament church. (3) Only Baptist churches can trace their lineage in uninterrupted fashion back to the New Testament, and only Baptist churches therefore are true churches. (4) If you want to see the Kingdom of God at work, look at Baptist churches for they are the only visible signs of the Kingdom of God. In fact Landmarkism insisted, Baptist churches and the Kingdom of God are really two sides of the same coin. (5) All other so-called churches are counterfeit, imitations, or "human societies" as the Landmarkers called them, and Baptists should have no dealings whatsoever with them. (6) Finally, only a true church-that is, a Baptist church-can legitimately celebrate the ordinances of baptism and the Lord's Supper. Any celebration of these ordinances by non-Baptists is invalid.

- ^ FitzGerald, Thomas E. (30 April 2004). The Ecumenical Movement: An Introductory History. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-0-313-05796-0.

Neither the American Baptist CHurches in the USA nor the more conservative Southern Baptist Convention have been active in Protestant union discussions. While the former is engaged in ecumenical activities, the latter has generally avoided ecumenical dialogues and associations.

- ^ Lord, Andy; Harris, I. Leon. "Network Church: A Pentecostal Ecclesiology Shaped by Mission". Themelios. 38 (1). Retrieved 28 February 2024.

- ^ 1689 London Baptist Confession

- ^ Savoy Declaration

- ^ "Brief Statement of the Doctrinal Position of the Missouri Synod". Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod. 1932. Sections 24–26. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ Andrew F. Walls (1996). Missionary Movement in Christian History: Studies in the Transmission of Faith. Orbis Books. ISBN 978-1-60833-106-2.

- ^ Robert, Dana L. (April 2000). "Shifting Southward: Global Christianity Since 1945". International Bulletin of Missionary Research. 24 (2): 50–58. doi:10.1177/239693930002400201. S2CID 152096915.

- ^ Jenkins, Philip (2011). The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199767465.

- ^ Kim, Sebastian; Kim, Kirsteen (2008). Christianity as a World Religion. London: Continuum. p. 2.

- ^ Jehu Hanciles (2008). Beyond Christendom: Globalization, African Migration, and the Transformation of the West. Orbis Books. ISBN 978-1-60833-103-1.

Bibliography

[edit]- University of Virginia: Dictionary of the History of Ideas: Christianity in History, retrieved May 10, 2007

- University of Virginia: Dictionary of the History of Ideas: Church as an Institution, retrieved May 10, 2007

- Christianity and the Roman Empire, Ancient History Romans, BBC Home, retrieved May 10, 2007 [13] Archived 2019-08-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Orthodox Church, MSN Encarta, retrieved May 10, 2007Orthodox Church – MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009.

- Catechism of the Catholic Church [14]

- Balmer, Randall Herbert (2002). Encyclopedia of Evangelicalism. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22409-7. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- Elwell, Walter; Comfort, Philip Wesley (2001). Tyndale Bible Dictionary. Tyndale House Publishers. ISBN 0-8423-7089-7.

- Mark Gstohl, Theological Perspectives of the Reformation, The Magisterial Reformation, retrieved May 10, 2007 [15]

- J. Faber, The Catholicity of the Belgic Confession, Spindle Works, The Canadian Reformed Magazine 18 (Sept. 20–27, Oct. 4–11, 18, Nov. 1, 8, 1969)-[16]

- Boise State University: History of the Crusades: The Fourth Crusade[17]

- United States Conference of Catholic Bishops: ARTICLE 9 "I BELIEVE IN THE HOLY CATHOLIC CHURCH": 830-831 [18]: Provides Catholic interpretations of the term catholic

- Kenneth D. Whitehead, Four Marks of the Church, EWTN Global Catholic Network [19]

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 330–345.

- Apostolic Succession, The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001–05.[20]

- Gerd Ludemann, Heretics: The Other Side of Early Christianity, Westminster John Knox Press, 1st American ed edition (August 1996), ISBN 0-664-22085-1, ISBN 978-0-664-22085-3

- From Jesus to Christ: Maps, Archaeology, and Sources: Chronology, PBS, retrieved May 19, 2007 [21]

- Bannerman, James, The Church of Christ: A treatise on the nature, powers, ordinances, discipline and government of the Christian Church, Still Waters Revival Books, Edmonton, Reprint Edition May 1991, First Edition 1869.

- Grudem, Wayne, Systematic Theology: An Introduction to Biblical Doctrine, Inter-Varsity Press, Leicester, England, 1994.

- Kuiper, R.B., The Glorious Body of Christ, The Banner of Truth Trust, Edinburgh, 1967

- Mannion, Gerard and Mudge, Lewis (eds.), The Routledge Companion to the Christian Church, 2007