Nikolai Gogol

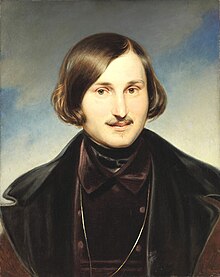

Portrait, early 1840s | |

| Born | Nikolai Vasilyevich Yanovsky 20 March 1809[a] (OS)/1 April 1809 (NS) Sorochyntsi, Russian Empire |

| Died | 21 February 1852 (aged 42) Moscow, Russian Empire |

| Resting place | Novodevichy Cemetery |

| Occupation | Playwright, short story writer, novelist |

| Language | Russian |

| Period | 1840–51 |

| Notable works | Full list |

| Signature | |

| |

Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol[b] (1 April [O.S. 20 March] 1809[a] – 4 March [O.S. 21 February] 1852) was a Russian novelist, short story writer, and playwright of Ukrainian origin.[2][3][4]

Gogol used the grotesque in his writings, for example, in his works "The Nose", "Viy", "The Overcoat", and "Nevsky Prospekt". These stories, and others such as "Diary of a Madman", have also been noted for their proto-surrealist qualities. According to Viktor Shklovsky, Gogol used the technique of defamiliarization when a writer presents common things in an unfamiliar or strange way so that the reader can gain new perspectives and see the world differently.[5] His early works, such as Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka, were influenced by his Ukrainian upbringing, Ukrainian culture and folklore.[6][7] His later writing satirised political corruption in contemporary Russia (The Government Inspector, Dead Souls), although Gogol also enjoyed the patronage of Tsar Nicholas I who liked his work.[8] The novel Taras Bulba (1835), the play Marriage (1842), and the short stories "The Tale of How Ivan Ivanovich Quarreled with Ivan Nikiforovich", "The Portrait", and "The Carriage" are also among his best-known works.

Many writers and critics have recognized Gogol's deep influence on Russian, Ukrainian and world literature. Gogol's influence was acknowledged by Fyodor Dostoevsky, Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, Franz Kafka, Mikhail Bulgakov, Vladimir Nabokov, Flannery O'Connor and others.[9][10] Eugène-Melchior de Vogüé said: "We all came out from under Gogol's Overcoat."

Early life

Gogol was born in the Ukrainian Cossack town of Sorochyntsi,[11] in the Poltava Governorate of the Russian Empire. His mother was descended from Leonty Kosyarovsky, an officer of the Lubny Regiment in 1710. His father Vasily Gogol-Yanovsky, who died when Gogol was 15 years old, was supposedly a descendant of Ukrainian Cossacks (see Lyzohub family) and belonged to the 'petty gentry'. Gogol knew that his paternal ancestor Ostap Hohol, a Cossack hetman in Polish service, received nobility from the Polish king.[12] The family used the Polish surname "Janowski" (Ianovskii) and the family estate in Vasilevka was known as Ianovshchyna.[12]

His father wrote poetry in Ukrainian as well as Russian, and was an amateur playwright in his own theatre. As was typical of the left-bank Ukrainian gentry of the early nineteenth century, the family was trilingual, speaking Ukrainian as well as Russian, and using Polish mostly for reading.[12] Mother was calling his son Nikola, which is a mixture of the Russian Nikolai and the Ukrainian Mykola.[12] As a child, Gogol helped stage plays in his uncle's home theater.[13]

In 1820, Nikolai Gogol went to a school of higher art in Nezhin (Nizhyn) (now Nizhyn Gogol State University) and remained there until 1828. It was there that he began writing. He was not popular among his schoolmates, who called him their "mysterious dwarf", but with two or three of them he formed lasting friendships. Very early he developed a dark and secretive disposition, marked by a painful self-consciousness and boundless ambition. Equally early he developed a talent for mimicry, which later made him a matchless reader of his own works and induced him to toy with the idea of becoming an actor.

On leaving school in 1828, Gogol went to Saint Petersburg, full of vague but ambitious hopes. He desired literary fame, and brought with him a Romantic poem of German idyllic life – Hans Küchelgarten, and had it published at his own expense, under the pseudonym "V. Alov." The magazines he sent it to almost universally derided it. He bought all the copies and destroyed them, swearing never to write poetry again.

Literary development

His stay in St. Petersburg forced Gogol to make a certain decision regarding his self-identification. It was a period of turmoil; the November Uprising in the lands of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth led to a rise of Russian nationalism.[12] Initially, Gogol used the surname Gogol-Ianovskii, but it soon became inconvenient. At first he tried to shorten it to the Russian-sounding "Ianov", but in the second half of 1830 he abandoned the Polish part of his surname altogether.[12] He even admonished his mother in a letter to address him only as "Gogol", as Poles had become "suspect" in St. Petersburg.[12] Tsarist authorities encouraged the Ukrainian intellectuals to sever ties with the Poles, promoting a limited, folkloric Ukrainian particularism as part of the heritage of the Russian empire.[12]

In 1831, the first volume of Gogol's Ukrainian stories (Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka) was published under a pen name "Rudy Panko", was in line with this trend, and met with immediate success.[14] A second volume was published in 1832, followed by two volumes of stories entitled Mirgorod in 1835, and two volumes of miscellaneous prose entitled Arabesques. At this time, Russian editors and critics such as Nikolai Polevoy and Nikolai Nadezhdin saw Gogol as a regional Ukrainian writer, and used his works to illustrate the specific of Ukrainian national characters.[13] The themes and style of these early prose works by Gogol, as well as his later drama, were similar to the work of Ukrainian-language writers and dramatists who were his contemporaries and friends, including Hryhory Kvitka-Osnovyanenko. However, Gogol's satire was much more sophisticated and unconventional.[15] Although these works were written in Russian, they were nevertheless full of Ukrainianisms, which is why a glossary of Ukrainian words was included at the end of the volumes.[16]

At this time, Gogol developed a passion for Ukrainian Cossack history and tried to obtain an appointment to the history department at Saint Vladimir Imperial University of Kiev.[17] Despite the support of Alexander Pushkin and Sergey Uvarov, the Russian minister of education, the appointment was blocked by a bureaucrat on the grounds that Gogol was unqualified.[18] His fictional story Taras Bulba, based on the history of Zaporozhian Сossacks, was the result of this phase in his interests. During this time, he also developed a close and lifelong friendship with the historian and naturalist Mykhaylo Maksymovych.[19]

In 1834, Gogol was made Professor of Medieval History at the University of St. Petersburg, a job for which he had no qualifications. The academic venture proved a disaster:

He turned in a performance ludicrous enough to warrant satiric treatment in one of his own stories. After an introductory lecture made up of brilliant generalizations which the 'historian' had prudently prepared and memorized, he gave up all pretence at erudition and teaching, missed two lectures out of three, and when he did appear, muttered unintelligibly through his teeth. At the final examination, he sat in utter silence with a black handkerchief wrapped around his head, simulating a toothache, while another professor interrogated the students.[20]

Gogol resigned his chair in 1835.

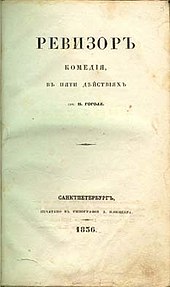

Between 1832 and 1836, Gogol worked with great energy, and had extensive contact with Pushkin, but he still had not yet decided that his ambitions were to be fulfilled by success in literature. During this time, the Russian critics Stepan Shevyrev and Vissarion Belinsky, contradicting the earlier critics, reclassified Gogol from a Ukrainian to a Russian writer.[13] It was only after the premiere of his comedy The Government Inspector (Revizor) at the Alexandrinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg, on 19 April 1836,[21] that he finally came to believe in his literary vocation. The comedy, a satire of Russian provincial bureaucracy, was staged thanks only to the intervention of the emperor, Nicholas I. The Tsar was personally present at the play's premiere, concluding that "there is nothing sinister in the comedy, as it is only a cheerful mockery of bad provincial officials."[22]

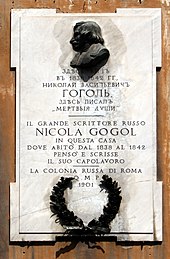

From 1836 to 1848, Gogol lived abroad, travelling through Germany and Switzerland. Gogol spent the winter of 1836–37 in Paris,[23] among Russian expatriates and Polish exiles, frequently meeting the Polish poets Adam Mickiewicz and Bohdan Zaleski.[24] He eventually settled in Rome. For much of the twelve years from 1836, Gogol was in Italy, where he developed an adoration for Rome. He studied art, read Italian literature and developed a passion for opera.

Pushkin's death produced a strong impression on Gogol. His principal work during the years following Pushkin's death was the satirical epic Dead Souls. Concurrently, he worked at other tasks – recast Taras Bulba (1842)[25] and The Portrait, completed his second comedy, Marriage (Zhenitba), wrote the fragment Rome and his most famous short story, "The Overcoat".

In 1841, the first part of Dead Souls was ready, and Gogol took it to Russia to supervise its printing. It appeared in Moscow in 1842, under a new title imposed by the censorship, The Adventures of Chichikov. The book established his reputation as one of the greatest prose writers in the language.

Later life

After the triumph of Dead Souls, Gogol's contemporaries came to regard him as a great satirist who lampooned the unseemly sides of Imperial Russia. They did not know that Dead Souls was but the first part of a planned modern-day counterpart to the Divine Comedy of Dante.[citation needed] The first part represented the Inferno; the second part would depict the gradual purification and transformation of the rogue Chichikov under the influence of virtuous publicans and governors – Purgatory.[26]

In April 1848, Gogol returned to Russia from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem and passed his last years in restless movement throughout the country. While visiting the capitals, he stayed with friends such as Mikhail Pogodin and Sergey Aksakov. During this period, he also spent much time with his old Ukrainian friends, Maksymovych and Osyp Bodiansky. He intensified his relationship with a starets or spiritual elder, Matvey Konstantinovsky, whom he had known for several years. Konstantinovsky seems to have strengthened in Gogol the fear of perdition (damnation) by insisting on the sinfulness of all his imaginative work.

Death

Exaggerated ascetic practices undermined his health and he became deeply depressed. On the night of 24 February 1852, he burned some of his manuscripts, which contained most of the second part of Dead Souls. He explained this as a mistake, a practical joke played on him by the Devil.[citation needed] Soon thereafter, he took to bed, refused all food, and died in great pain nine days later.

Gogol was mourned in the Saint Tatiana church at the Moscow University before his burial and then buried at the Danilov Monastery, close to his fellow Slavophile Aleksey Khomyakov. His grave was marked by a large stone (Golgotha), topped by a Russian Orthodox cross.[27]

In 1931, with Russia now ruled by communists, Moscow authorities decided to demolish the monastery and had Gogol's remains transferred to the Novodevichy Cemetery.[28] His body was discovered lying face down, which gave rise to the conspiracy theory that Gogol had been buried alive. The authorities moved the Golgotha stone to the new gravesite, but removed the cross; in 1952, the Soviets replaced the stone with a bust of Gogol. The stone was later reused for the tomb of Gogol's admirer Mikhail Bulgakov. In 2009, in connection with the bicentennial of Gogol's birth, the bust was moved to the museum at the Novodevichy Cemetery, and the original Golgotha stone was returned, along with a copy of the original Orthodox cross.[29]

The first Gogol monument in Moscow, a Symbolist statue on Arbat Square, represented the sculptor Nikolay Andreyev's idea of Gogol rather than the real man.[30] Unveiled in 1909, the statue received praise from Ilya Repin and from Leo Tolstoy as an outstanding projection of Gogol's tortured personality. Everything changed after the October Revolution. Joseph Stalin did not like the statue, and it was replaced by a more orthodox Socialist Realist monument in 1952.[31] It took enormous efforts to save Andreyev's original work from destruction; as of 2014[update] it stands in front of the house where Gogol died.[32]

Style

D. S. Mirsky characterizes Gogol's universe as "one of the most marvellous, unexpected – in the strictest sense, original[33] – worlds ever created by an artist of words".[34]

Gogol saw the outer world strangely metamorphosed, a singular gift particularly evident from the fantastic spatial transformations in his Gothic stories, "A Terrible Vengeance" and "A Bewitched Place". His pictures of nature are strange mounds of detail heaped on detail, resulting in an unconnected chaos of things: "His people are caricatures, drawn with the method of the caricaturist – which is to exaggerate salient features and to reduce them to geometrical pattern. But these cartoons have a convincingness, a truthfulness, and inevitability – attained as a rule by slight but definitive strokes of unexpected reality – that seems to beggar the visible world itself."[35] According to Andrey Bely, Gogol's work influenced the emergence of Gothic romance, and served as a forerunner for absurdism and impressionism.[36]

The aspect under which the mature Gogol sees reality is expressed by the Russian word poshlost', which means something similar to "triviality, banality, inferiority", moral and spiritual, widespread in a group of people or the entire society. Like Sterne before him, Gogol was a great destroyer of prohibitions and of romantic illusions. He undermined Russian Romanticism by making vulgarity reign where only the sublime and the beautiful had before.[37] "Characteristic of Gogol is a sense of boundless superfluity that is soon revealed as utter emptiness and a rich comedy that suddenly turns into metaphysical horror."[38] His stories often interweave pathos and mockery, while "The Tale of How Ivan Ivanovich Quarreled with Ivan Nikiforovich" begins as a merry farce and ends with the famous dictum "It is dull in this world, gentlemen!"

Politics

It stunned Gogol when some critics interpreted The Government Inspector as an indictment of Tsarism despite Nicholas I's patronage of the play. Gogol himself, an adherent of the Slavophile movement, believed in a divinely inspired mission for both the House of Romanov and the Russian Orthodox Church. Like Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Gogol sharply disagreed with those Russians who preached constitutional monarchy and the disestablishment of the Orthodox Church. Gogol saw his work as a critique that would change Russia for the better.[39]

After defending autocracy, serfdom, and the Orthodox Church in his book Selected Passages from Correspondence with his Friends (1847), Gogol came under attack from his former patron Vissarion Belinsky. The first Russian intellectual to publicly preach the economic theories of Karl Marx, Belinsky accused Gogol of betraying his readership by defending the status quo.[40]

National identity

Gogol was born in the Ukrainian Cossack town of Sorochyntsi. According to Edyta Bojanowska, Gogol's images of Ukraine are in-depth, distinguished by description of folklore and history. In his Evenings on a Farm, Gogol pictures Ukraine as a "nation ... united by organic culture, historical memory, and language". His image of Russia lacks this depth and is always based in the present, particularly focused on Russia's bureaucracy and corruption. Dead Souls, according to Bojanowska, "presents Russian uniqueness as a catalog of faults and vices."[41] The duality of Gogol’s national identity is frequently expressed as a view that "in the aesthetic, psychological, and existential senses Gogol is inscribed ... into Ukrainian culture", while "in historical and cultural terms he is part of Russian literature and culture".[42] Slavicist Edyta Bojanowska writes that Gogol, after arriving in St. Petersburg, was surprised to find that he was perceived as a Ukrainian, and even as a khokhol (hick). Bojanowska argues that it was this experience that "made him into a self-conscious Ukrainian". According to Ilchuk, dual national identities were typical at that time as a "compromise with the empire's demand for national homogenization".[43]

Professor of Russian literature Kathleen Scollins notes the tendency to politicize Gogol's identity, and comments on the erasure of Gogol's Ukrainianness by the Russian literary establishment, which she argues "reveals the insecurity of many Russians about their own imperial identity". According to Scollins, Gogol's narrative double-voicedness in both Evenings and Taras Bulba and "pidginized Russian" of the Zaporizhian Cossacks in "The Night before Christmas represents a "strateg[y] of resistance, self-assertion, and divergence"".[44] Linguist Daniel Green notes "the complexities of an imperial culture in which Russian and Ukrainian literatures and identities informed and shaped each other, with Gogol´ playing a key role in these processes".[45]

Gogol's appreciation of Ukraine grew during his discovery of Ukrainian history, and he concluded that "Ukraine possessed exactly the kind of cultural wholeness, proud tradition, and self-awareness that Russia lacked." He rejected or was critical of many of the postulates of official Russian history about Ukrainian nationhood. His unpublished "Mazepa’s Meditations" presents Ukrainian history in a manner that justifies Ukraine’s "historic right to independence". Before 1836, Gogol had planned to move to Kyiv to study Ukrainian ethnography and history, and it was after these plans failed that he decided to become a Russian writer.[41]

Professor of literature and Gogol researcher Oleh Ilnytzkyj also argues against the traditional classification of Nikolai Gogol as a Russian writer, saying that he should be viewed as a Ukrainian writer operating within an imperial culture. The "Russian" view of Gogol, he contends, arises from "all-Russianness," an ideology aimed at assimilating the East Slavs into a singular "Russian" nation. Gogol was appropriated by an underdeveloped Russian literature, which downplayed his Ukrainian heritage and nationalism to bolster its own prestige. Ilnytzkyj emphasizes that Russian functioned as an imperial lingua franca rather than a marker of nationality, serving as a literary language adopted by Ukrainian society to advance a Ukrainian national agenda before Ukrainian became the preferred option. He refutes the notion that Gogol’s Ukrainian and Russian works reflect a "divided soul," portraying them instead as unified expressions of Ukrainian nationalism—rooted in a deep love for Ukraine and disdain for Russia, from which he self-exiled for twelve years. Gogol’s struggle, Ilnytzkyj argues, was not with his identity but with the demands placed on him by Russian imperial expectations.[46]

In his interpretation of Taras Bulba (1842), Ilnytzkyj argues that the second edition of the novel is a profound assertion of Ukrainian nationalism, supported by a meticulous examination of Gogol’s use of terms such as russkii, Rossiia, and tsar'. According to Ilnytzkyj, Gogol deliberately linked his Ukrainian Cossack characters to the legacy of Kyivan Rus’, crafting a distinct Ukrainian-Rus’ian identity with the term russkii—a direct challenge to the "all-Russian" narrative advanced by Russian imperial ideology. While Gogol’s legacy occupies a place in both Ukrainian and Russian literary traditions, Ilnytzkyj cautions against confusing his dual influence with a hyphenated identity, emphasizing instead Gogol’s fundamental Ukrainian identity within a transnational imperial framework. Finally, Ilnytzkyj asserts that nothing Gogol wrote after 1842 undermines his identity as a Ukrainian writer. After publishing Dead Souls and the revised Taras Bulba, Gogol ceased to function as an artist, despite attempts to sustain his earlier creative efforts. His later non-fiction, shaped by a religious crisis and pressure to revise his views on Russia, cannot negate the Ukrainian nationalist and anti-Russian achievements of his earlier fiction.[46]

Influence and interpretations

Even before the publication of Dead Souls, Belinsky recognized Gogol as the first Russian-language realist writer and as the head of the natural school, to which he also assigned younger or lesser authors such as Goncharov, Turgenev, Dmitry Grigorovich, Vladimir Dahl and Vladimir Sollogub. Gogol himself appeared skeptical about the existence of such a literary movement. Although he recognized "several young writers" who "have shown a particular desire to observe real life", he upbraided the deficient composition and style of their works.[47] Nevertheless, subsequent generations of radical critics celebrated Gogol (the author in whose world a nose roams the streets of the Russian capital) as a great realist, a reputation decried by the Encyclopædia Britannica as "the triumph of Gogolesque irony".[48]

The period of literary modernism saw a revival of interest in and a change of attitude towards Gogol's work. One of the pioneering works of Russian formalism was Eichenbaum's reappraisal of "The Overcoat". In the 1920s, a group of Russian short-story writers, known as the Serapion Brothers, placed Gogol among their precursors and consciously sought to imitate his techniques. The leading novelists of the period – notably Yevgeny Zamyatin and Mikhail Bulgakov – also admired Gogol and followed in his footsteps. In 1926, Vsevolod Meyerhold staged The Government Inspector as a "comedy of the absurd situation", revealing to his fascinated spectators a corrupt world of endless self-deception. In 1934, Andrei Bely published the most meticulous study of Gogol's literary techniques up to that date, in which he analyzed the colours prevalent in Gogol's work depending on the period, his impressionistic use of verbs, the expressive discontinuity of his syntax, the complicated rhythmical patterns of his sentences, and many other secrets of his craft. Based on this work, Vladimir Nabokov published a summary account of Gogol's masterpieces.[49]

Gogol's impact on Russian literature has endured, yet various critics have appreciated his works differently. Belinsky, for instance, berated his horror stories as "moribund, monstrous works", while Andrei Bely counted them among his most stylistically daring creations. Nabokov especially admired Dead Souls, The Government Inspector, and "The Overcoat" as works of genius, proclaiming that "when, as in his immortal 'The Overcoat', Gogol really let himself go and pottered happily on the brink of his private abyss, he became the greatest artist that Russia has yet produced."[50] Critics traditionally interpreted "The Overcoat" as a masterpiece of "humanitarian realism", but Nabokov and some other attentive readers argued that "holes in the language" make the story susceptible to interpretation as a supernatural tale about a ghostly double of a "small man".[51] Of all Gogol's stories, "The Nose" has stubbornly defied all abstruse interpretations: D.S. Mirsky declared it "a piece of sheer play, almost sheer nonsense". In recent years, however, "The Nose" has become the subject of several postmodernist and postcolonial interpretations.

The portrayals of Jewish characters in his work have led to Gogol developing a reputation for antisemitism. Due to these portrayals, the Russian Zionist writer Ze'ev Jabotinsky condemned Russian Jews who participated in celebrations of Gogol's centenary. Later critics have also pointed to the apparent antisemitism in his writings, as well as in those of his contemporary, Fyodor Dostoyevsky.[52] Felix Dreizin and David Guaspari, for example, in their The Russian Soul and the Jew: Essays in Literary Ethnocentrism, discuss "the significance of the Jewish characters and the negative image of the Ukrainian Jewish community in Gogol's novel Taras Bulba, pointing out Gogol's attachment to anti-Jewish prejudices prevalent in Russian and Ukrainian culture."[53] In Léon Poliakov's The History of Antisemitism, the author mentions that

"The 'Yankel' from Taras Bulba indeed became the archetypal Jew in Russian literature. Gogol painted him as supremely exploitative, cowardly, and repulsive, albeit capable of gratitude. But it seems perfectly natural in the story that he and his cohorts be drowned in the Dniper by the Cossack lords. Above all, Yankel is ridiculous, and the image of the plucked chicken that Gogol used has made the rounds of great Russian authors."[54]

Despite his portrayal of Jewish characters, Gogol left a powerful impression even on Jewish writers who inherited his literary legacy. Amelia Glaser has noted the influence of Gogol's literary innovations on Sholem Aleichem, who

"chose to model much of his writing, and even his appearance, on Gogol... What Sholem Aleichem was borrowing from Gogol was a rural East European landscape that may have been dangerous, but could unite readers through the power of collective memory. He also learned from Gogol to soften this danger through laughter, and he often rewrites Gogol's Jewish characters, correcting anti-Semitic stereotypes and narrating history from a Jewish perspective."[55]

In music and film

Gogol's oeuvre has also had an impact on Russia's non-literary culture, and his stories have been adapted numerous times into opera and film. The Russian composer Alfred Schnittke wrote the eight-part Gogol Suite as incidental music to The Government Inspector performed as a play, and Dmitri Shostakovich set The Nose as his first opera in 1928 – a peculiar choice of subject for what was meant to initiate the great tradition of Soviet opera.[56] More recently, to celebrate the 200th anniversary of Gogol's birth in 1809, Vienna's renowned Theater an der Wien commissioned music and libretto for a full-length opera on the life of Gogol from Russian composer and writer Lera Auerbach.[57]

More than 135 films[58] have been based on Gogol's work, the most recent being The Girl in the White Coat (2011).

Legacy

Gogol has been featured many times on Russian and Soviet postage stamps; he is also well represented on stamps worldwide.[59][60][61][62] Several commemorative coins have been issued in the USSR and Russia. In 2009, the National Bank of Ukraine issued a commemorative coin dedicated to Gogol.[63] Streets have been named after Gogol in various cities, including Moscow, Sofia, Lipetsk, Odesa, Myrhorod, Krasnodar, Vladimir, Vladivostok, Penza, Petrozavodsk, Riga, Bratislava, Belgrade, Harbin and many other towns and cities.

Gogol is mentioned several times in Fyodor Dostoyevsky's Poor Folk and Crime and Punishment and Chekhov's The Seagull.

Ryūnosuke Akutagawa considered Gogol along with Edgar Allan Poe his favorite writers.

Adaptations

BBC Radio 4 made a series of six Gogol short stories, entitled Three Ivans, Two Aunts and an Overcoat (2002, adaptations by Jim Poyser) starring Griff Rhys-Jones and Stephen Moore. The stories adapted were "The Two Ivans", "The Overcoat", "Ivan Fyodorovich Shponka and His Aunt", "The Nose", "The Mysterious Portrait" and "Diary of a Madman".

Gogol's short story "Christmas Eve" (literally the Russian title «Ночь перед Рождеством» translates as "The Night before Christmas") was adapted into operatic form by at least three East Slavic composers. Ukrainian composer Mykola Lysenko wrote his Christmas Eve («Різдвяна ніч», with libretto in Ukrainian by Mykhailo Starytsky) in 1872. Just two years later, in 1874, Tchaikovsky composed his version under the title Vakula the Smith (with Russian libretto by Yakov Polonsky) and revised it in 1885 as Cherevichki (The Tsarina's Slippers). In 1894 (i.e., just after Tchaikovsky's death), Rimsky-Korsakov wrote the libretto and music for his own opera based on the same story. "Christmas Eve" was also adapted into a film in 1961 entitled The Night Before Christmas. It was adapted also for radio by Adam Beeson and broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on 24 December 2008[64] and subsequently rebroadcast on both Radio 4 and Radio 4 Extra on Christmas Eve 2010, 2011 and 2015.[65]

Gogol's story "Viy" was adapted into film by Russian filmmakers four times: the original Viy in 1967; the horror film Vedma (aka The Power of Fear) in 2006; the action-horror film Viy in 2014; and the horror film Gogol Viy, released in 2018. It was also adapted into the Russian full-motion video game Viy: The Story Retold (2004). Outside of Russia, the film loosely served as the inspiration for Mario Bava's 1960 film Black Sunday and the 2008 South Korean horror film Evil Spirit ; VIY.

In 2016, Gogol's short story "The Portrait" was announced to be adapted into a feature film of the same name, by Anastasia Elena Baranoff and Elena Vladimir Baranoff.[66][67][68][69][70][71]

The Russian TV-3 television series Gogol features Nikolai Gogol as a lead character and presents a fictionalized version of his life that mixes his history with elements from his various stories.[72] The episodes were also released theatrically starting with Gogol. The Beginning in August 2017. A sequel entitled Gogol. Viy was released in April 2018, and the third film, Gogol. Terrible Revenge, debuted in August 2018.

In 1963, an animated version of Gogol's classic surrealist story "The Nose" was made by Alexandre Alexeieff and Claire Parker, using the pinscreen animation technique, for the National Film Board of Canada.[73] A definitive animated movie adaptation of the story was released in January 2020. Meanwhile, The Nose or Conspiracy of Mavericks has been in production for about fifty years.[74]

Bibliography

Notes

- ^ a b Some sources indicate he was born 19/31 March 1809.

- ^ /ˈɡoʊɡəl, ˈɡoʊɡɔːl/;[1] Russian: Николай Васильевич Гоголь, IPA: [nʲɪkɐˈlaj vɐˈsʲilʲjɪvʲɪdʑ ˈɡoɡəlʲ]; Ukrainian: Микола Васильович Гоголь, romanized: Mykola Vasyliovych Hohol; né Yanovsky (Russian: Яновский; Ukrainian: Яновський, romanized: Yanovskyi

Citations

- ^ "Gogol". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Bojanowska, Edyta M. (2007). "Introduction". Nikolai Gogol: Between Ukrainian and Russian Nationalism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 1–13. ISBN 9780674022911.

- ^ Fanger, Donald (30 June 2009). The Creation of Nikolai Gogol. Harvard University Press. pp. 24, 87–88. ISBN 9780674036697. pp. 24, 87–88:

Gogol left Russian literature on the brink of that golden age of fiction which many deemed him to have originated, and to which he did, very clearly, open the way. The literary situation he entered, however, was very different, and one cannot understand the shape and sense of Gogol's career—the peripeties of his lifelong devotion to being a Russian writer, the singularity and depth of his achievement—without knowing something of that situation. ... Romantic theory exalted ethnography and folk poetry as expressions of the Volksgeist, and the Ukraine was particularly appealing to a Russian audience in this respect, being, as Gippius observes, a country both '"ours" and "not ours," neighboring, related, and yet lending itself to presentation in the light of a semi-realistic romanticism, a sort of Slavic Ausonia.' Gogol capitalized on this appeal as a mediator; by embracing his Ukrainian heritage, he became a Russian writer.

- ^ Vaag, Irina (9 April 2009). "Gogol: russe et ukrainien en même temps" [Gogol: Russian and Ukrainian at the same time]. L'Express (Interview with Vladimir Voropaev) (in French). Retrieved 2 April 2021.

Il ne faut pas diviser Gogol. Il appartient en même temps à deux cultures, russe et ukrainienne...Gogol se percevait lui-même comme russe, mêlé à la grande culture russe...En outre, à son époque, les mots "Ukraine" et "ukrainien" avaient un sens administratif et territorial, mais pas national. Le terme "ukrainien" n'était presque pas employé. Au XIXe siècle, l'empire de Russie réunissait la Russie, la Malorossia (la petite Russie) et la Biélorussie. Toute la population de ses régions se nommait et se percevait comme russe.

[We must not divide Gogol. He belongs at the same time to two cultures, Russian and Ukrainian...Gogol perceived himself as Russian, mingled with the great Russian culture...Furthermore, in his era, the words "Ukraine" and "Ukrainian" had an administrative and territorial meaning, but not national. The term "Ukrainian" was almost never used. In the nineteenth century, the Russian Empire comprised Russia, Malorossia (Little Russia) and Byelorussia. The whole population of these regions called themselves, and perceived themselves as, Russian.] - ^ Viktor Shklovsky. String: On the dissimilarity of the similar. Moscow: Sovetsky Pisatel, 1970. – p. 230.

- ^ Ilnytzkyj, Oleh. "The Nationalism of Nikolai Gogol': Betwixt and Between?", Canadian Slavonic Papers Sep–Dec 2007. Retrieved 15 June 2008.

- ^ Karpuk, Paul A. "Gogol's Research on Ukrainian Customs for the Dikan'ka Tales". Russian Review, Vol. 56, No. 2 (April 1997), pp. 209–232.

- ^ "Очень нервный вечер. Как Николай I и Гоголь постановку «Ревизора» смотрели" (in Russian). Argumenty i Fakty. 1 May 2016.

- ^ "Natural School (Натуральная школа)". Brief Literary Encyclopedia in 9 Volumes. Moscow. 1968. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ Nikolai Gogol // Concise Literary Encyclopedia in 9 volumes.

- ^ "Nikolay Gogol". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bojanowska 2012, p. 160.

- ^ a b c Bojanowska, Edyta M. (2007). Nikolai Gogol: Between Ukrainian and Russian Nationalism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 78–88. ISBN 9780674022911.

- ^ Krys Svitlana, “Allusions to Hoffmann in Gogol’s Ukrainian Horror Stories from the Dikan'ka Collection.” Canadian Slavonic Papers: Special Issue, devoted to the 200th anniversary of Nikolai Gogol'’s birth (1809–1852) 51.2–3 (June–September 2009): 243–266.

- ^ Richard Peace (30 April 2009). The Enigma of Gogol: An Examination of the Writings of N.V. Gogol and Their Place in the Russian Literary Tradition. Cambridge University Press. pp. 151–152. ISBN 978-0-521-11023-5. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ^ Bojanowska 2012, p. 160-161.

- ^ Bojanowska 2012, p. 161.

- ^ Luckyj, G. (1998). The Anguish of Mykola Ghoghol, a.k.a. Nikolai Gogol. Toronto: Canadian Scholars' Press. p. 67. ISBN 1-55130-107-5.

- ^ "Welcome to Ukraine". Wumag.kiev.ua. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ Lindstrom, T. (1966). A Concise History of Russian Literature Volume I from the Beginnings to Checkhov. New York: New York University Press. p. 131. LCCN 66-22218.

- ^ "The Government Inspector" (PDF). American Conservative Theater. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ "Очень нервный вечер. Как Николай I и Гоголь постановку «Ревизора» смотрели" (in Russian). Argumenty i Fakty. 1 May 2016.

- ^ RBTH (24 June 2013). "Le nom de Nikolaï Gogol est immortalisé à la place de la Bourse à Paris" (in French). Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ^ Bojanowska 2012, p. 165.

- ^ Ilnytzkyj, Oleh S. (2010–2011). "Is Gogol's 1842 Version of Taras Bul'ba really 'Russified'?". Journal of Ukrainian Studies. 35–36: 51–68.

- ^ Gogol declared that "the subject of Dead Souls has nothing to do with the description of Russian provincial life or of a few revolting landowners. It is for the time being a secret which must suddenly and to the amazement of everyone (for as yet none of my readers has guessed it) be revealed in the following volumes..."

- ^ Могиле Гоголя вернули первозданный вид: на нее поставили "Голгофу" с могилы Булгакова и восстановили крест.(in Russian)

- ^ "Novodevichy Cemetery". Passport Magazine. April 2008. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ Могиле Гоголя вернули первозданный вид: на нее поставили "Голгофу" с могилы Булгакова и восстановили крест.(in Russian) Retrieved 23 September 2013

- ^ Российское образование. Федеральный образовательный портал: учреждения, программы, стандарты, ВУЗы, тесты ЕГЭ. Archived 4 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- ^ "Зачем Сталин убрал памятник Гоголю в Москве" (in Russian). rg.ru. 1 June 2017.

- ^ For a full story and illustrations, see Российское образование. Федеральный образовательный портал: учреждения, программы, стандарты, ВУЗы, тесты ЕГЭ. Archived 17 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian) and Москва и москвичи Archived 13 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- ^ This does not mean that numerous influences cannot be discerned in his work. The principle of these are: the tradition of the Ukrainian folk and puppet theatre, with which the plays of Gogol's father were closely linked; the heroic poetry of the Cossack ballads (dumy), the Iliad in the Russian version by Gnedich; the numerous and mixed traditions of comic writing from Molière to the vaudevillians of the 1820s; the picaresque novel from Lesage to Narezhny; Sterne, chiefly through the medium of German romanticism; the German romanticists themselves (especially Tieck and E.T.A. Hoffmann); the French tradition of Gothic romance – a long and yet incomplete list.[citation needed]

- ^ D.S. Mirsky. A History of Russian Literature. Northwestern University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8101-1679-0. p. 155.

- ^ Mirsky, p. 191

- ^ Andrey Bely (1934). The Mastery Of Gogol (in Russian). Leningrad: Ogiz.

- ^ According to some critics, Gogol's grotesque is a "means of estranging, a comic hyperbole that unmasks the banality and inhumanity of ambient reality". See: Fusso, Susanne. Essays on Gogol: Logos and the Russian Word. Northwestern University Press, 1994. ISBN 0-8101-1191-8. p. 55.

- ^ "Russian literature." Encyclopædia Britannica, 2005.

- ^ "Очень нервный вечер. Как Николай I и Гоголь постановку «Ревизора» смотрели" (in Russian). Argumenty i Fakty. 1 May 2016.

- ^ "Letter to N.V. Gogol". marxists.org. February 2008. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ a b Bojanowska, Edyta M. (28 February 2007). Nikolai Gogol: Between Ukrainian and Russian Nationalism. Harvard University Press. pp. 370, 371. ISBN 978-0-674-02291-1.

The strength of Gogol's commitment to Ukraine before 1836 is also reflected in his plans to move to Kiev in order to devote himself to ethnographic and historic research on Ukraine. Only when these plans fell through did Gogol decide to become a Russian writer, a role that he understood as concomitant to serving Russian nationalism.

- ^ Ilchuk, Yuliya (26 February 2021). Nikolai Gogol: Performing Hybrid Identity. University of Toronto Press. pp. 3–18, 167–172. ISBN 978-1-4875-0825-8.

- ^ Ueland, Carol; Trigos, Ludmilla A. (14 March 2022). Literary Biographies in The Lives of Remarkable People Series in Russia: Biography for the Masses. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 95, 96. ISBN 978-1-7936-1830-6.

- ^ Scollins, Kathleen (2022). "Nikolai Gogol: Performing Hybrid Identity by Yuliya Ilchuk (review)". Pushkin Review. 24 (1): 97–101. doi:10.1353/pnr.2022.a903273. ISSN 2165-0683.

- ^ Green, Daniel (2023). "Nikolai Gogol: Performing Hybrid Identity by Yuliya Ilchuk (review)". Slavonic and East European Review. 101 (4): 784–785. doi:10.1353/see.2023.a923986. ISSN 2222-4327.

- ^ a b Ilnytzkyj, Oleh S. (22 July 2024). Nikolai Gogol: Ukrainian Writer in the Empire: A Study in Identity. De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783111373263. ISBN 978-3-11-137326-3.

- ^ "The structure of the stories themselves seemed especially unskilful and clumsy to me; in one story I noted excess and verbosity, and an absence of simplicity in the style". Quoted by Vasily Gippius in his monograph Gogol (Duke University Press, 1989, p. 166).

- ^ The latest edition[which?] of the Britannica labels Gogol "one of the finest comic authors of world literature and perhaps its most accomplished nonsense writer." See under "Russian literature."[citation needed]

- ^ Nabokov, Vladimir (2017) [1961]. Nikolai Gogol. New York: New Directions. p. 140. ISBN 0-8112-0120-1

- ^ Nabokov, Vladimir (2017) [1961]. Nikolai Gogol. New York: New Directions. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-8112-0120-9.

- ^ Dostoevsky appears to have had such a reading of the story in mind when he wrote The Double. The quote, often apocryphally attributed to Dostoevsky, that "we all [future generations of Russian novelists] emerged from Gogol's Overcoat", actually refers to those few who read "The Overcoat" as a ghost story (as did Aleksey Remizov, judging by his story The Sacrifice).

- ^ Vladim Joseph Rossman, Vadim Rossman, Vidal Sassoon. Russian Intellectual Antisemitism in the Post-Communist Era. p. 64. University of Nebraska Press. Google.com

- ^ "Antisemitism in Literature and in the Arts". Sicsa.huji.ac.il. Archived from the original on 26 September 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ Léon Poliakov. The History of Antisemitism. p. 75. University of Pennsylvania Press, Google.com

- ^ Amelia Glaser. "Sholem Aleichem, Gogol Show Two Views of Shtetl Jews." The Jewish Journal, 2009. Journal: Jewish News, Events, Los Angeles

- ^ Gogol Suite, CD Universe

- ^ "Zwei Kompositionsaufträge vergeben" [Two Compositions Commissioned]. wien.orf.at (in German). Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Alt URL

- ^ "Nikolai Gogol". IMDb.

- ^ "ru:200 лет со дня рождения Н.В.Гоголя (1809–1852), писателя" [200 years since the birth of Nikolai Gogol (1809–1852), writer] (in Russian). marka-art.ru. 1 April 2009. Archived from the original on 22 March 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2009.

- ^ К 200-летию со дня рождения Н.В. Гоголя выпущены почтовые блоки [Stamps issued for the 200th anniversary of N.V. Gogol's birthday]. kraspost.ru (in Russian). 2009. Archived from the original on 17 March 2012. Retrieved 3 April 2009.

- ^ Зчіпка 200-річчя від дня народження Миколи Гоголя (1809–1852) [Coupling for the 200th anniversary of the birth of Mykola Hohol (1809–1852)]. Марки (in Ukrainian). Ukrposhta. Retrieved 3 April 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Украина готовится достойно отметить 200-летие Николая Гоголя [Ukraine is preparing to celebrate the 200th anniversary of Nikolai Gogol's birth] (in Russian). otpusk.com. 28 August 2006. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ^ Events by themes: NBU presented an anniversary coin «Nikolay Gogol» from series "Personages of Ukraine", UNIAN-photo service (19 March 2009)

- ^ "Christmas Eve". BBC Radio 4. 24 December 2008. Archived from the original on 10 January 2009.

- ^ Gogol, Nikolai (24 December 2015). "Nikolai Gogol – Christmas Eve". BBC Radio 4 Extra. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ^ "Patrick Cassavetti boards Lenin?!".

- ^ "Gogol's short story The Portrait to be made into feature film". russianartandculture.com. 4 July 2014. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ^ Screen International [1], Berlin Film Festival, 12 February 2016.

- ^ Russian Art and Culture “Gogol’s “The Portrait” adapted for the screen by an international team of talents” Archived 1 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine, London, 29 January 2016.

- ^ Kinodata.Pro [2] Archived 3 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine Russia, 12 February 2016.

- ^ Britshow.com [3] Archived 29 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine 16 February 2016.

- ^ "Сериал о Гоголе собрал за первые выходные в четыре раза больше своего бюджета". Vedomosti.

- ^ Nowell-Smith, Geoffrey, ed. (1996). The Oxford History of World Cinema. Oxford University Press. p. 274. ISBN 978-0-19-874242-5. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ "Если бы речь шла только об отрицании, пароход современности далеко бы не уплыл". Коммерсантъ. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

References

- Townsend, Dorian Aleksandra, From Upyr' to Vampire: The Slavic Vampire Myth in Russian Literature, Ph.D. Dissertation, School of German and Russian Studies, Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences, University of New South Wales, May 2011.

This article incorporates text from D.S. Mirsky's "A History of Russian Literature" (1926-27), a publication now in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from D.S. Mirsky's "A History of Russian Literature" (1926-27), a publication now in the public domain.

Further reading

- Bojanowska, Edyta (2012). "Nikolai Vasilievich Gogol (1809–1852)". In Norris, Stephen M.; Sunderland, Willard (eds.). Russia's People of Empire: Life stories from Eurasia, 1500 to the present. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-00176-4.

- Poliukhovych, Olha (20 February 2023). "Stolen identity: how Nikolai Gogol usurped Mykola Hohol". Prospect. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

External links

Media related to Nikolai Gogol at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Nikolai Gogol at Wikimedia Commons- Works by Nikolai Gogol in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Nikolai Gogol at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Nikolai Gogol at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Nikolai Gogol at IMDb

- Gogol : Magical realism

- Petri Liukkonen. "Nikolai Gogol". Books and Writers.

- Nikolay Gogol in Encyclopædia Britannica

- A manuscript of part of Gogol's Dead Souls, held by the Library of Congress

- Gogol House at Google Cultural Institute

- Nikolai Gogol

- 1809 births

- 1852 deaths

- People from Poltava Oblast

- People from Mirgorodsky Uyezd

- Eastern Orthodox writers

- Magic realism writers

- Mythopoeic writers

- Dramatists and playwrights from the Russian Empire

- Russian male dramatists and playwrights

- Russian satirists

- Russian satirical novelists

- Monarchists from the Russian Empire

- Russian male novelists

- Russian male short story writers

- Ukrainian novelists

- Ukrainian satirists

- Ukrainian satirical novelists

- 19th-century short story writers from the Russian Empire

- 19th-century writers from the Russian Empire

- Nizhyn Gogol State University alumni

- Saint Petersburg State University alumni

- Burials at Novodevichy Cemetery

- Ukrainian male writers