Manuel L. Quezon

Manuel L. Quezon | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

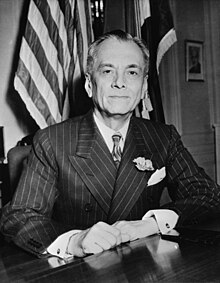

Quezon in 1942 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2nd President of the Philippines | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 15 November 1935 – 1 August 1944 Serving with Jose P. Laurel (1943–1944)[a] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vice President | Sergio Osmeña | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Emilio Aguinaldo Frank Murphy (as Governor-General) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Secretary of National Defense | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 16 July 1941 – 11 December 1941 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President | Himself | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Teófilo Sison | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Jorge B. Vargas | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mayor of Quezon City | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Acting | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 12 October 1939 – 4 November 1939 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vice Mayor | Vicente Fragante | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Position established | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Tomas Morato | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Secretary of Public Instruction | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 1 December 1938 – 19 April 1939 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President | Himself | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Sergio Osmeña | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Jorge Bocobo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Manuel Luis Quezon y Molina 19 August 1878 Baler, El Príncipe, Nueva Écija, Captaincy General of the Philippines, Spanish East Indies (now Baler, Aurora, Philippines) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 1 August 1944 (aged 65) Saranac Lake, New York, U.S. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cause of death | Tuberculosis | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Nacionalista (1907–1944) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relatives | Manuel L. Quezon III (grandson) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Education | Colegio de San Juan de Letran | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | University of Santo Tomas | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Military service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Allegiance | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Branch/service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years of service |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Battles/wars | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

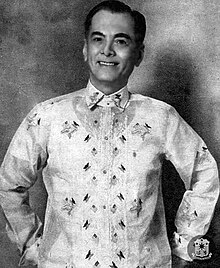

Manuel Luis Quezon y Molina[b] GCGH KGCR (UK: /ˈkeɪzɒn/, US: /ˈkeɪsɒn, -sɔːn, -soʊn/, Tagalog: [maˈnwel luˈis ˈkɛson], Spanish: [maˈnwel ˈlwis ˈkeson]; 19 August 1878 – 1 August 1944), also known by his initials MLQ, was a Filipino lawyer, statesman, soldier, and politician who was president of the Commonwealth of the Philippines from 1935 until his death in 1944. He was the first Filipino to head a government of the entire Philippines and is considered the second president of the Philippines after Emilio Aguinaldo (1899–1901), whom Quezon defeated in the 1935 presidential election. He is often regarded as the greatest President of the Philippines, and the quintessential Filipino statesman.

During his presidency, Quezon tackled the problem of landless peasants. Other major decisions included the reorganization of the islands' military defense, approval of a recommendation for government reorganization, the promotion of settlement and development in Mindanao, dealing with the foreign stranglehold on Philippine trade and commerce, proposals for land reform, and opposing graft and corruption within the government. He established a government in exile in the U.S. with the outbreak of World War II and the threat of Japanese invasion. Scholars have described Quezon's leadership as a "de facto dictatorship"[2] and described him as "the first Filipino politician to integrate all levels of politics into a synergy of power" after removing his term limits as president and turning the Senate into an extension of the executive through constitutional amendments.[3]

In 2015, the Board of the International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation bestowed a posthumous Wallenberg Medal on Quezon and the people of the Philippines for reaching out to victims of the Holocaust from 1937 to 1941. President Benigno Aquino III and then-94-year-old Maria Zenaida Quezon-Avanceña, the daughter of the former president, were informed of this recognition.[4]

Early life and education

[edit]

Quezon was born on 19 August 1878 in Baler in the district of El Príncipe,[5] then the capital of Nueva Ecija (now Baler, Aurora). His parents were Lucio Quezon y Vélez (1850–1898) and María Dolores Molina (1840–1893).[6] Both were primary-school teachers, although his father was a retired sargento de Guardia Civil (sergeant of the Civil Guard).

According to historian Augusto de Viana in his timeline of Baler, Quezon's father was a Chinese mestizo who came from the Parián (a Chinatown outside Intramuros) in Paco, Manila. He spoke Spanish in the Civil Guard and married María, who was a Spanish mestiza born of Spanish priest Jose Urbina de Esparragosa; Urbina arrived in Baler from Esparragosa de la Serena, Cáceres Province, Spain in 1847 as the parish priest.[7] Quezon is Chinese mestizo surname originally from a Spanish romanization of Hokkien Chinese, possibly from the Hokkien word, Chinese: 雞孫; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: ke-sun / koe-sun, with Chinese: 雞; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: ke meaning "outer city" or "strongest" and Chinese: 孫; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: sun meaning "grandson";[8][9] many Filipino surnames that end with “on”, “son”, and “zon” are of Chinese origin, Hispanized version of 孫 (sun).[10]

He later boarded at the Colegio de San Juan de Letran, where he graduated from secondary school in 1894.[11]

In 1899, Quezon left his law studies at the University of Santo Tomas to join the Filipino war effort, and joined the Republican army during the Philippine–American War. He was an aide-de-camp to Emilio Aguinaldo.[12] Quezon became a major, and fought in the Bataan sector. After surrendering in 1900,[13] he returned to university and passed the bar examination in 1903.[14]

Quezon worked for a time as a clerk and surveyor, entering government service as treasurer for Mindoro and (later) Tayabas. He became a municipal councilor of Lucena, and was elected governor of Tayabas in 1906.[15]

Congressional career

[edit]House of Representatives (1907–1916)

[edit]

Quezon was elected in 1907 to represent Tayabas's 1st district in the first Philippine Assembly (which later became the House of Representatives) during the 1st Philippine Legislature, where he was majority floor leader and chairman of the committees on rules and appropriations. Quezon told the U.S. House of Representatives during a 1914 discussion of the Jones Bill that he received most of his primary education at the village school established by the Spanish government as part of the Philippines' free public-education system.[16] Months before his term ended, he gave up his seat at the Philippine Assembly upon being appointed as one of the Philippines' two resident commissioners. Serving two terms from 1909 to 1916, he lobbied for the passage of the Philippine Autonomy Act (the Jones Law).[11]

Senate (1916–1935)

[edit]

Quezon returned to Manila in 1916, and was elected senator from the Fifth Senatorial District. He was later elected Senate President and served continuously until 1935 (19 years), the longest tenure in history until Senator Lorenzo Tañada's four consecutive terms (24 years, from 1947 to 1972). Quezon headed the first independent mission to the U.S. Congress in 1919, and secured passage of the Tydings–McDuffie Act in 1934.[17]

Rivalry with Osmeña

[edit]In 1921, Quezon made a public campaign against House Speaker Sergio Osmeña accusing him of being an autocratic leader and blamed him for the Philippine National Bank's financial mess. Both Osmeña and Quezon debated on this until 1922. As a result, the Nationalista Party was split into two. Quezon also resigned as Senate President that same year in January.[18]

In 1922, he became leader of the Nacionalista Party alliance Partido Nacionalista-Colectivista.[17]

In 1933, both Quezon and Osmeña clashed regarding the ratification of the Hare–Hawes–Cutting bill in the Philippine Legislature.[19][20]

Presidency (1935–1944)

[edit]| Presidential styles of Manuel L. Quezon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Excellency[21] |

| Spoken style | Your Excellency |

| Alternative style | Mr. President |

Administration and cabinet

[edit]First term (1935–1941)

[edit]

In 1935, Quezon won the Philippines' first national presidential election under the Nacionalista Party. He received nearly 68 percent of the vote against his two main rivals, Emilio Aguinaldo and Gregorio Aglipay. Quezon, inaugurated on November 15, 1935,[22] is recognized as the second President of the Philippines. In January 2008, however, House Representative Rodolfo Valencia (Oriental Mindoro–1st) filed a bill seeking to declare General Miguel Malvar the second Philippine President; Malvar succeeded Aguinaldo in 1901.[23]

Supreme Court appointments

[edit]Under the Reorganization Act, Quezon was given the power to appoint the first all-Filipino cabinet in 1935. From 1901 to 1935, a Filipino was chief justice but most Supreme Court justices were Americans. Complete Filipinization was achieved with the establishment of the Commonwealth of the Philippines in 1935. Claro M. Recto and José P. Laurel were among Quezon's first appointees to replace the American justices. Membership in the Supreme Court increased to 11: a chief justice and ten associate justices, who sat en banc or in two divisions of five members each.

- Ramón Avanceña – 1935 (Chief Justice) – 1935–1941

- José Abad Santos – 1935

- Claro M. Recto – 1935–1936

- José P. Laurel – 1935

- José Abad Santos (Chief Justice) – 1941–1942

Government reorganization

[edit]To meet the demands of the newly-established government and comply with the Tydings-McDuffie Act and the Constitution, Quezon, – true to his pledge of "more government and less politics," – initiated a reorganization of the government.[24] He established a Government Survey Board to study existing institutions and, in light of changed circumstances, make necessary recommendations.[24]

Early results were seen with the revamping of the executive department; offices and bureaus were merged or abolished, and others were created.[24] Quezon ordered the transfer of the Philippine Constabulary from the Department of the Interior to the Department of Finance. Other changes were made to the National Defense, Agriculture and Commerce, Public Works and Communications, and Health and Public Welfare departments.[24]

New offices and boards were created by executive order or legislation.[24] Among these were the Council of National Defense,[25] the Board of National Relief,[26] the Mindanao and Sulu Commission, and the Civil Service Board of Appeals.[24][27]

Social-justice program

[edit]Pledging to improve the conditions of the Philippine working class and inspired by the social doctrines of Pope Leo XIII and Pope Pius XI and treatises by the world's leading sociologists, Quezon began a program of social justice introduced with executive measures and legislation by the National Assembly.[24] A court for industrial relations was established to mediate disputes, minimizing the impact of strikes and lockouts. A minimum-wage law was enacted, as well as a law providing an eight-hour workday and a tenancy law for Filipino farmers. The position of public defender was created to assist the poor.[24]

Commonwealth Act No. 20 enabled Quezon to acquire large, occupied estates to re-appropriate their lots and homes at a nominal cost and under terms affordable by their residents; one example was the Buenavista estate. He also began a cooperative system of agriculture among owners of the subdivided estates to increase their income.[24] [28] Quezon desired to follow the constitutional mandate on the promotion of social justice.[24]

Economy

[edit]When the Commonwealth was created, its economy was stable and promising.[24] With foreign trade peaking at ₱400 million, the upward trend in business resembled a boom. Export crops were generally good and, except for tobacco, were in high demand. The value of Philippine exports reached ₱320,896,000, the highest since 1929.[24]

Government revenue in 1936 was ₱76,675,000 (equivalent to ₱34,858,669,716 in 2021), compared to the 1935 revenue of ₱65,000,000 (equivalent to ₱28,793,209,590 in 2021). Government companies, except for the Manila Railroad Company, earned profits. Gold production increased about 37 percent, iron nearly doubled, and cement production increased by about 14 percent.[24]

The government had to address some economic problems, however,[24] and the National Economic Council was created. It advised the government about economic and financial questions, including the promotion of industries, diversification of crops and enterprises, tariffs, taxation, and formulating an economic program in preparation for eventual independence.[24] The National Development Company was reorganized by law, and the National Rice and Corn Company (NARIC) was created with a ₱4 million budget.[24]

Upon the recommendation of the National Economic Council, agricultural colonies were established in Koronadal, Malig, and other locations in Mindanao. The government encouraged migration and settlement in the colonies.[24] The Agricultural and Industrial Bank was established to aid small farmers with convenient loans and affordable terms.[29] Attention was paid to soil surveying and the disposition of public land.[24]

Land reform

[edit]When the commonwealth government was established, Quezon implemented the Rice Share Tenancy Act of 1933 to regulate share-tenancy contracts by establishing minimum standards.[30][31] The act provided a better tenant-landlord relationship, a 50–50 sharing of the crop, regulation of interest at 10 percent per agricultural year, and protected against arbitrary dismissal by the landlord.[30] Because of a major flaw in the act, however, no petition to apply it was ever presented.[30]

The flaw was that it could be used only when the majority of municipal councils in a province petitioned for it.[30] Since landowners usually controlled such councils, no province ever asked that the law be applied. Quezon ordered that the act be mandatory in all Central Luzon provinces.[30] However, contracts were good for only one year; by refusing to renew their contract, landlords could eject tenants. Peasant organizations clamored in vain for a law which would make a contract automatically renewable as long as tenants fulfilled their obligations.[30] The act was amended to eliminate this loophole in 1936, but it was never carried out; by 1939, thousands of peasants in Central Luzon were threatened with eviction.[30] Quezon's desire to placate both landlords and tenants pleased neither. Thousands of tenants in Central Luzon were evicted from their farmlands by the early 1940s, and the rural conflict was more acute than ever.[30]

During the Commonwealth period, agrarian problems persisted.[30] This motivated the government to incorporate a social-justice principle into the 1935 Constitution. Dictated by the government's social-justice program, expropriation of estates and other landholdings began. The National Land Settlement Administration (NLSA) began an orderly settlement of public agricultural lands. At the outbreak of the Second World War, settlement areas covering over 65,000 hectares (250 sq mi) had been established.[30]

Educational reforms

[edit]With his Executive Order No. 19, dated 19 February 1936, Quezon created the National Council of Education. Rafael Palma, former president of the University of the Philippines, was its first chairman.[24][32] Funds from the early Residence Certificate Law were devoted to maintaining public schools throughout the country and opening many more. There were 6,511 primary schools, 1,039 intermediate schools, 133 secondary and special schools, and five junior colleges by this time. Total enrollment was 1,262,353, with 28,485 teachers. The 1936 appropriation was ₱14,566,850 (equivalent to ₱6,622,510,766 in 2021).[24] Private schools taught over 97,000 students, and the Office of Adult Education was created.[24]

Women's suffrage

[edit]

Quezon initiated women's suffrage during the Commonwealth era.[33] As a result of prolonged debate between proponents and opponents of women's suffrage, the constitution provided that the issue be resolved by women in a plebiscite. If at least 300,000 women voted for the right to vote, it would be granted. The plebiscite was held on 30 April 1937; there were 447,725 affirmative votes, and 44,307 opposition votes.[33]

National language

[edit]The Philippines' national language was another constitutional question. After a one-year study, the Institute of National Language recommended that Tagalog be the basis for a national language. The proposal was well-received, despite the fact that director Jaime C. de Veyra was Waray, this is because Baler, Quezon's birthplace, is a native Tagalog-speaking area.

In December 1937, Quezon issued a proclamation approving the institute's recommendation and declaring that the national language would become effective in two years. With presidential approval, the INL began work on a Tagalog grammar text and dictionary.[33]

Visits to Japan (1937–1938)

[edit]As Imperial Japan encroached on the Philippines, Quezon antagonized neither the American nor the Japanese officials. He travelled twice to Japan as president, from 31 January to 2 February 1937 and from 29 June to 10 July 1938, to meet with government officials. Quezon emphasized that he would remain loyal to the United States, assuring protection of the rights of the Japanese who resided in the Philippines. Quezon's visits may have signalled the Philippines' inclination to remain neutral in the event of a Japanese-American conflict if the U.S. disregarded the country's concerns. [34]

Council of State expansion

[edit]In 1938, Quezon expanded the Council of State in Executive Order No. 144.[33][35] This highest of advisory bodies to the president would be composed of the President, Vice President, Senate President, House Speaker, Senate President pro tempore, House Speaker pro tempore, the majority floor leaders of both chambers of Congress, former presidents, and three to five prominent citizens.[33]

1938 midterm election

[edit]The elections for the Second National Assembly were held on 8 November 1938 under a new law which allowed block voting[36] and favored the governing Nacionalista Party. As expected, all 98 assembly seats went to the Nacionalistas. José Yulo, Quezon's Secretary of Justice from 1934 to 1938, was elected speaker.

The Second National Assembly intended to pass legislation strengthening the economy, but the Second World War clouded the horizon; laws passed by the First National Assembly were modified or repealed to meet existing realities.[37][38] A controversial immigration law which set an annual limit of 50 immigrants per country,[39] primarily affecting Chinese and Japanese nationals escaping the Sino-Japanese War, was passed in 1940. Since the law affected foreign relations, it required the approval of the U.S. president. When the 1939 census was published, the National Assembly updated the apportionment of legislative districts; this became the basis for the 1941 elections.

1939 plebiscite

[edit]On 7 August 1939, the United States Congress enacted a law in accordance with the recommendations of the Joint Preparatory Commission on Philippine Affairs. Because the new law required an amendment of the Ordinance appended to the Constitution, a plebiscite was held on 24 August 1939. The amendment received 1,339,453 votes in favor, and 49,633 against.[33]

Third official language

[edit]

Quezon had established the Institute of National Language (INL) to create a national language for the country. On 30 December 1937, in Executive Order No. 134, he declared Tagalog the Philippines' national language; it was taught in schools during the 1940–1941 academic year. The National Assembly later enacted Law No. 570, making the national language an official language with English and Spanish; this became effective on 4 July 1946, with the establishment of the Philippine Republic.[33][40]

1940 plebiscites

[edit]With the 1940 local elections, plebiscites were held for proposed amendments to the constitution about a bicameral legislature, the presidential term (four years, with one re-election, and the establishment of an independent Commission on Elections. The amendments were overwhelmingly ratified. Speaker José Yulo and Assemblyman Dominador Tan traveled to the United States to obtain President Franklin D. Roosevelt's approval, which they received on 2 December 1940. Two days later, Quezon proclaimed the amendments.

1941 presidential election

[edit]Quezon was originally barred by the Philippine constitution from seeking re-election. In 1940, however, a constitutional amendment was ratified which allowed him to serve a second term ending in 1943. In the 1941 presidential election, Quezon was re-elected over former Senator Juan Sumulong with nearly 82 percent of the vote. He was inaugurated on December 30, 1941 at the Malinta Tunnel in Corregidor.[41] The oath of office was administered by Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines José Abad Santos. Corregidor was chosen as the venue of the inauguration and temporary seat of the government in-exile to take refuge from the uninterrupted Japanese bombing raids during the Japanese invasion.[42]

Second term (1941–1944)

[edit]Pre-war activity

[edit]As crises mounted in the Pacific, the Philippines prepared for war. Youth military training under General Douglas MacArthur was intensified. The first blackout practice was held on the night of 10 July 1941 in Manila. First aid was taught in all schools and social clubs. Quezon established the Civilian Emergency Administration (CEA) on 1 April 1941, with branches in provinces and towns.[43] Air-raid drills were also held.

Jewish refugees

[edit]

In cooperation with U.S. High Commissioner Paul V. McNutt, Quezon facilitated the entry into the Philippines of Jewish refugees fleeing fascist regimes in Europe and took on critics who were convinced by propaganda that Jewish settlement was a threat to the country.[44][45][46] Quezon and McNutt proposed 30,000 refugee families on Mindanao and 30,000-40,000 refugees on Polillo. Quezon made a 10-year loan to Manila's Jewish Refugee Committee of land adjacent to his family home in Marikina to house homeless refugees in Marikina Hall (the present-day Philippine School of Business Administration), which was dedicated on 23 April 1940.[47]

Government in exile

[edit]

After the Japanese invasion of the Philippines during World War II,[48] Quezon evacuated to Corregidor (where he was inaugurated for his second term) and then to the Visayas and Mindanao. At the invitation of the U.S. government,[49] he was evacuated to Australia,[50] and then to the United States. Quezon established the Commonwealth government in exile, with its headquarters in Washington, D.C. He was a member of the Pacific War Council, signed the United Nations declaration against the Axis powers and wrote The Good Fight, his autobiography.[33]

To conduct government business in exile, Quezon hired the entire floor of one wing of the Shoreham Hotel to accommodate his family and his office. Government offices were established at the quarters of Philippine Resident Commissioner Joaquin Elizalde, who became a member of Quezon's wartime cabinet. Other cabinet appointees were Brigadier-General Carlos P. Romulo as Secretary of the Department of Information and Public Relations and Jaime Hernandez as Auditor General.[33]

Sitting under a canvas canopy outside the Malinta Tunnel on 22 January 1942, Quezon heard a fireside chat during which President Roosevelt said that the Allied forces were determined to defeat Berlin and Rome, followed by Tokyo. Quezon was infuriated, summoned General MacArthur and asked him if the U.S. would support the Philippines; if not, Quezon would return to Manila and allow himself to become a prisoner of war. MacArthur replied that if the Filipinos fighting the Japanese learned that he returned to Manila and became a Japanese puppet, they would consider him a turncoat.[51]

Quezon then heard another broadcast by former president Emilio Aguinaldo urging him and his fellow Filipino officials to yield to superior Japanese forces. Quezon wrote a message to Roosevelt saying that he and his people had been abandoned by the U.S. and it was Quezon's duty as president to stop fighting. MacArthur learned about the message, and ordered Major General Richard Marshall to counterbalance it with American propaganda whose purpose was the "glorification of Filipino loyalty and heroism".[52]

On 2 June 1942, Quezon addressed the United States House of Representatives about the necessity of relieving the Philippine front. He did the same to the Senate, urging the senators to adopt the slogan "Remember Bataan". Despite his declining health, Quezon traveled across the U.S. to remind the American people about the Philippine war.[33]

Wartime

[edit]

Quezon broadcast a radio message to Philippine residents in Hawaii, who purchased ₱4 million worth of war bonds, for his first birthday celebration in the United States.[33] Indicating the Philippine government's cooperation with the war effort, he offered the U.S. Army a Philippine infantry regiment which was authorized by the War Department to train in California. Quezon had the Philippine government acquire Elizalde's yacht; renamed Bataan and crewed by Philippine officers and sailors, it was donated to the United States for use in the war.[33]

In early November 1942, Quezon conferred with Roosevelt on a plan for a joint commission to study the post-war Philippine economy. Eighteen months later, the United States Congress passed an act creating the Philippine Rehabilitation Commission.[33]

Quezon-Osmeña impasse

[edit]By 1943, the Philippine government in exile was faced with a crisis.[33] According to the 1935 constitution, Quezon's term would expire on 30 December 1943 and Vice-President Sergio Osmeña would succeed him as president. Osmeña wrote to Quezon advising him of this, and Quezon issued a press release and wrote to Osmeña that a change in leadership would be unwise at that time. Osmeña then requested the opinion of U.S. Attorney General Homer Cummings, who upheld Osmeña's view as consistent with the law. Quezon remained adamant, and sought President Roosevelt's decision. Roosevelt remained aloof from the controversy, suggesting that the Philippine officials resolve the impasse.[33]

Quezon convened a cabinet meeting with Osmeña, Resident Commissioner Joaquín Elizalde, Brigadier General Carlos P. Romulo and his cabinet secretaries, Andrés Soriano and Jaime Hernandez. After a discussion, the cabinet supported Elizalde's position in favor of the constitution, and Quezon announced his plan to retire in California.[33]

After the meeting, Osmeña approached Quezon and broached his plan to ask the United States Congress to suspend the constitutional provisions for presidential succession until after the Philippines had been liberated; this legal way out was agreeable to Quezon and his cabinet, and steps were taken to carry out the proposal. Sponsored by Senator Tydings and Congressman Bell, the resolution was unanimously approved by the Senate on a voice vote and passed the House of Representatives by a vote of 181 to 107 on 10 November 1943.[33] He was inaugurated for the third time on November 15, 1943 in Washington, D.C. The oath of office was administered by US Associate Justice Felix Frankfurter.[53]

Death and burial

[edit]

Quezon had developed tuberculosis and spent his last years in hospitals, including a Miami Beach Army hospital in April 1944.[54] That summer, he was at a cure cottage in Saranac Lake, New York. Quezon died there at 10:05 a.m. ET on 1 August 1944, at age 65. His remains were initially buried in Arlington National Cemetery, but his body was brought by former Governor-General and High Commissioner Frank Murphy aboard the USS Princeton and re-interred in the Manila North Cemetery on 17 July 1946.[55] Those were then moved to a miniature copy of Napoleon's tomb[56] at the Quezon Memorial Shrine in Quezon City, on 1 August 1979.[57]

Electoral history

[edit]| Candidate | Party | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manuel L. Quezon | Nacionalista Party | 695,332 | 67.98 | |

| Emilio Aguinaldo | National Socialist Party | 179,349 | 17.53 | |

| Gregorio Aglipay | Republican Party | 148,010 | 14.47 | |

| Pascual Racuyal | Independent | 158 | 0.02 | |

| Total | 1,022,849 | 100.00 | ||

| Candidate | Party | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manuel L. Quezon | Nacionalista Party | 1,340,320 | 80.14 | |

| Juan Sumulong | Popular Front (Sumulong wing)[c] | 298,608 | 17.85 | |

| Celerino Tiongco I | Ganap Party | 22,474 | 1.34 | |

| Hilario Moncado | Modernist Party | 10,726 | 0.64 | |

| Hermogenes Dumpit | Independent | 298 | 0.02 | |

| Veronica Miciano | Independent | 62 | 0.00 | |

| Ernesto T. Belleza | Independent | 16 | 0.00 | |

| Pedro Abad Santos[d] | Popular Front (Abad Santos wing)[c] | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Total | 1,672,504 | 100.00 | ||

- ^ Laurel was president of the Second Philippine Republic, a puppet government set up by Imperial Japan, while Quezon was president of the government in exile. Laurel's presidency was retroactively recognized by succeeding Philippine governments.

- ^ In this Spanish name, the first or paternal surname is Quezon and the second or maternal family name is Molina.

- ^ a b The Popular Front was split into two wings: those who supported Pedro Abad Santos or the "Abad Santos wing" and those who supported Juan Sumulong or the "Sumulong wing".

- ^ Withdrew

Personal life

[edit]

Quezon was married to his first cousin, Aurora Aragón Quezon, on 17 December 1918. They had four children: María Aurora "Baby" Quezon (23 September 1919 – 28 April 1949), María Zenaida "Nini" Quezon-Avanceña (9 April 1921 – 12 July 2021), Luisa Corazón Paz "Nenita" Quezon (17 February – 14 December 1924) and Manuel L. "Nonong" Quezon, Jr. (23 June 1926 – 18 September 1998).[58] His grandson, Manuel L. "Manolo" Quezon III (born 30 May 1970), a writer and former undersecretary of the Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office, was named after him.

Awards and honors

[edit]The Foreign Orders, Medals and Decorations of President Manuel L. Quezon:

- Foreign Awards

France:

France:  : Légion d'honneur, Officer[58]

: Légion d'honneur, Officer[58] Mexico:

Mexico:  : Order of the Aztec Eagle, Collar

: Order of the Aztec Eagle, Collar Belgium:

Belgium:  : Order of the Crown, Grand Cross

: Order of the Crown, Grand Cross Spain:

Spain:  : Orden de la República Española, Grand Cross

: Orden de la República Española, Grand Cross Republic of China:

Republic of China:  : Order of Brilliant Jade, Grand Cordon

: Order of Brilliant Jade, Grand Cordon

- National Honors

: Order of the Golden Heart, Grand Collar (Maringal na Kuwintas) - 19 August 1960[59]

: Order of the Golden Heart, Grand Collar (Maringal na Kuwintas) - 19 August 1960[59] : Order of the Knights of Rizal, Knight Grand Cross of Rizal (KGCR)[60]

: Order of the Knights of Rizal, Knight Grand Cross of Rizal (KGCR)[60]

-

Foreign Orders and Decorations of Quezon displayed in the Presidential Museum and Library

-

Quezon taking the Oath of Office at his Inauguration at the Legislative Building on November 15, 1935

-

Quezon delivering his Inaugural Address at the Legislative Building on November 15, 1935 in Manila

Legacy

[edit]Quezon City, the province of Quezon, Quezon Bridge in Manila, Manuel L. Quezon University, and many streets are named after him. The Quezon Service Cross is the Philippines' highest honor. Quezon is memorialized on Philippine currency, appearing on the Philippine twenty-peso note and two commemorative 1936 one-peso coins: one with Frank Murphy and another with Franklin Delano Roosevelt.[61] Open Doors, a Holocaust memorial in Rishon LeZion, Israel, is a 7-metre-tall (23 ft) sculpture designed by Filipino artist Luis Lee Jr. It was erected in honor of Quezon and the Filipinos who saved over 1,200 Jews from Nazi Germany.[62][63]

Municipalities in six provinces are named after Quezon: Quezon, Bukidnon; Quezon, Isabela; Quezon, Nueva Ecija; Quezon, Nueva Vizcaya; Quezon, Palawan; and Quezon, Quezon. The Presidential Papers of Manuel L. Quezon was inscribed in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register in 2011.[64] Quezon Island is the most developed island in the Hundred Islands National Park.[65]

Annually on 19 August, Manuel L. Quezon Day is celebrated throughout the Philippines as a special working holiday, except for the provinces of Quezon (including Lucena) and Aurora and Quezon City, where it is a non-working holiday.[66][67] His birthplace Baler is now part of Aurora, which was a sub-province of Quezon and was named after his cousin and wife.

-

The Quezon Service Cross, the Philippines' highest civilian honor

-

Monument in Lucena

-

Time cover, 1935

-

1978 birth-centenary stamp

-

Commemorative ₱50 coin released in 1978

-

₱20 coin introduced in 2019

-

₱200 English series banknote

-

The 1935 Cadillac V-16 car of President Quezon displayed at the Presidential Car Museum

In popular culture

[edit]Quezon was played by Richard Gutierrez in the 2010 music video of the Philippine national anthem produced and aired by GMA Network.[68] Arnold Reyes played him in the musical MLQ: Ang Buhay ni Manuel Luis Quezon (2015).[69] Quezon was played by Benjamin Alves in the film, Heneral Luna (2015).[70] Alves and TJ Trinidad portrayed him in the 2018 film Goyo: Ang Batang Heneral (2018).[71] Quezon was played by Raymond Bagatsing in the film Quezon's Game (2019).[72]

Speech recording

[edit]A sample of Quezon's voice is preserved in a recorded speech, "Message to My People", which he delivered in English and Spanish.[73] Quezon recorded it while he was President of the Senate "in the 1920s, when he was first diagnosed with tuberculosis and assumed he didn't have much longer to live," according to his grandson Manuel L. Quezon III.[74]

See also

[edit]- List of Asian Americans and Pacific Islands Americans in the United States Congress

- List of Hispanic and Latino Americans in the United States Congress

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Philippine Education. F.R. Lutz. 1917.

- ^ Pante, Michael D. (26 January 2017). "Quezon's City: Corruption and contradiction in Manila's prewar suburbia, 1935–1941". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 48 (1): 91–112. doi:10.1017/S0022463416000497. S2CID 151565057.

- ^ McCoy, Alfred (1988). Quezon's Commonwealth: The Emergence of Philippine Authoritarianism.

- ^ "Quezon feted for rescuing Jews". The Manila Times. 19 August 2015.

- ^ National Historical Commission of the Philippines. "History of Baler". National Historical Commission of the Philippines. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

When military district of El Príncipe was created in 1856, Baler became its capital...On June 12, 1902 a civil government was established, moving the district of El Príncipe away from the administrative jurisdiction of Nueva Ecija...and placing it under the jurisdiction of Tayabas Province.

- ^ McCoy, Alfred W. (15 October 2009). Policing America's Empire: The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 581. ISBN 978-0-299-23413-3. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ Flores, Wilson Lee (13 July 2008). "Love in the time of war: Manuel Quezon's dad, Anne Curtis, Jericho Rosales & Ed Angara in Baler". PhilStar Global Sunday Lifestyle. Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ Behind the Name: Quezon

- ^ QUEZON is the Spanish transliteration of Hokkien for “the strongest grandson” in Instagram

- ^ El Pilipinismo: Chino Cristiano Surnames

- ^ a b "QUEZON, Manuel L." US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives. Office of the Historian, Clerk of the House's Office of Art and Archives. Archived from the original on 8 September 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ Office of History and Preservation, United States Congress. (n.d.). Quezon, Manuel Luis, (1878–1944). Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved 30 September 2010.

- ^ Reyes, Pedrito (1953). Pictorial History of the Philippines.

- ^ "The Letran Awards". Colegio de San Juan de Letran. President Manuel Quezon Award- Government Service Award. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ "Manuel L. Quezon". Malacañang. Archived from the original on 12 October 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ Quezon, Manuel Luis (1915). "Escuelas públicas durante el régimen español" [Public schools during the Spanish regime]. Philippine Assembly, Third Legislature, Third Session, Document No.4042-A 87 Speeches of Manuel L. Quezon, Philippine resident commissioner, delivered in the House of Representatives of the United States during the discussion of Jones Bill, 26 September-14 October 1914 [Asamblea Filipina, Tercera Legislatura, Tercer Período de Sesiones, Documento N.o 4042-A 87, Discursos del Manuel L. Quezon, comisionado residente de Filipinas, Pronunciados en la Cámara de representantes de los Estados Unidos con motivo de la discusión del Bill Jones, 26, septiembre-14, octubre, 1914] (in Spanish). Manila, Philippines: Bureau of Printing. p. 35. Archived from the original on 1 December 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

... there were public schools in the Philippines long before the American occupation, and, in fact, I have been educated in one of these schools, even though my hometown is such a small town, isolated in the mountains of the Northeastern part of the island of Luzon. (Spanish). [... había escuelas públicas en Filipinas mucho antes de la ocupación americana, y que, de hecho, yo me había educado en una de esas escuelas, aunque mi pueblo natal es un pueblo tan pequeño, aislado en las montañas de la parte Noreste de la isla de Luzón.]

- ^ a b Bowman, John S., ed. (2000). Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture. Columbia University Press. p. 494. ISBN 0231500041. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ^ Gripaldo, Rolando M. (1991). "The Quezon-Osmeña Split of 1922". Philippine Studies. 39 (2): 158–175. ISSN 0031-7837.

- ^ Gripaldo, Rolando (2017). "Quezon and Osmeña on the Hare-Hawes Cutting and Tydings-McDuffie Act" (PDF). Quezon-Winslow Correspondence and Other Essays.

- ^ The Freeman. "Sergio Osmeña, Sr". Philstar.com. Retrieved 3 January 2025.

- ^ "Official Program Aquino Inaugural (Excerpts)". Archived from the original on 12 February 2015.

- ^ "Inaugural Address of President Manuel L. Quezon, November 15, 1935". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. 15 November 1935. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ Cruz, Maricel (2 January 2008). "Lawmaker: History wrong on Gen. Malvar". Archived from the original on 6 April 2008. Retrieved 2 May 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Molina, Antonio M. (1961). The Philippines Through the Centuries (Print ed.). Manila: University of Santo Tomas Cooperative.

- ^ "Commonwealth Act No. 1". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. 21 December 1935. Archived from the original on 18 November 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ "Executive Order No. 61, s. 1936". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. 3 November 1936. Archived from the original on 25 March 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ "Executive Order No. 39, s. 1936". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. 23 June 1936. Archived from the original on 25 March 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ "Commonwealth Act No. 20". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. 11 July 1936. Archived from the original on 24 March 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ "C.A. No. 459: An Act Creating the Agricultural and Industrial Bank". The Corpus Juris. 9 June 1939. Archived from the original on 18 August 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Manapat, Carlos L. (2010). Economics, Taxation, and Agrarian Reform. C & E Publishing, Incorporated. ISBN 978-971-584-989-0. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ "Act No. 4054". Chan Robles Virtual Law Library. Archived from the original on 23 January 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ "Executive Order No. 19, s. 1936". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. 19 February 1936. Archived from the original on 25 March 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Molina, Antonio (1961). The Philippines: Through the centuries (Print ed.). University of Santo Tomas Cooperative.

- ^ Yu-Jose, Lydia (1998). Philippine-Japan Relations: the Revolutionary Years and a Century Hence in Philippine External Relations: A Centennial Vista. Foreign Service Institute.

- ^ "Executive Order No. 144, s. 1938". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. 17 March 1938. Archived from the original on 25 March 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ "Block voting". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 10 September 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Commonwealth Act (CA) No. 494 amended CA 444, the "Eight Hour Law", authorizing the president to suspend it.

- ^ "C.A. No. 494: An Act to Authorize the President of the Philippines to Suspend, Until We Date of Adjournment of the Next Regular Session of the National Assembly Either Wholly or Partially the Operation of Commonwealth Act Numbered Four Hundred and Forty-Four, Commonly Known as the Eight-Hour Labor Law". The Corpus Juris. 30 September 1939. Archived from the original on 25 March 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ "Commonwealth Act No. 613". Chan Robles Virtual Law Library. Archived from the original on 10 December 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ "Executive Order No. 134, s. 1937". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. 30 December 1937. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ Second Inaugural Address of President Quezon (Speech). Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. 30 December 1941. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ "Jose Abad Santos". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ^ Ricklefs, M. C.; Lockhart, Bruce; Lau, Albert (19 November 2010). A New History of Southeast Asia. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 298. ISBN 978-1-137-01554-9. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ Peñamante, Laurice (7 June 2017). "Nine Waves of Refugees in the Philippines - UNHCR Philippines". United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Archived from the original on 24 July 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ^ Rodis, Rodel (13 April 2013). "Philippines: A Jewish refuge from the Holocaust". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 2 May 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ^ Berger, Joseph (14 February 2005). "A Filipino-American Effort to Harbor Jews Is Honored". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 June 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ Quezon III, Manuel L. (30 May 2019). "Jewish Refugees and the Philippines, a timeline: nationalism, propaganda, war". ABS-CBN News. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Evacuation flights may be identified at the AirForceHistoryIndex.org site Archived 4 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine by searching for Quezon

- ^ 1st Lt William Haddock Campbell, USAAF, received the DSC for his role as co-pilot in the evacuation of the Philippine president from the Philippines, as reported in a local Chicago newspaper, The Garfieldian, 1 April 1943 edition.

- ^ Quezon, Manuel L. Jr. (8 December 2001). "Escape from Corregidor, December 8, 2001". philippinesfreepress.wordpress.com. Archived from the original on 21 April 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ Manchester, William (2008). American Caesar: Douglas MacArthur 1880–1964. Back Bay Books. p. 245.

- ^ Manchester 2008, p. 246.

- ^ "Inaugural Address of President Manuel L. Quezon, November 15, 1943". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. 15 November 1943. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ "The Miami News – Google News Archive Search". google.com.

- ^ "Official Month in Review: July 1946". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Office of the President of the Philippines. July 1946. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ "Paranormal and Historical". Archived from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- ^ "Museo ni Manuel Quezon". National Historical Commission of the Philippines. Archived from the original on 7 October 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- ^ a b The Commercial & Industrial Manual of the Philippines; 1940-1941. Manila: Publishers incorporated. 1938. p. 10. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ "Roster of Recipients of Presidential Awards". Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ "Our Story". Knights of Rizal. Archived from the original on 15 June 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ^ "Picture of commemorative coin". Caimages.collectors.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ Park, Madison (2 February 2015). "How the Philippines saved 1,200 Jews during Holocaust". CNN. Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ Contreras, Volt (31 December 2010). "Monument in Israel Honors Filipinos". Asian Journal. Manila: Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ "Presidential Papers of Manuel L. Quezon". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^ "31 Interesting Facts About Hundred Islands National Park - Jacaranda's Travels - Philippines Tourists Spots". Jacarandatravels.com. 25 May 2016. Archived from the original on 10 April 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ "Proclamation No. 2105, s. 1981". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. 18 August 1981. Archived from the original on 19 March 2023. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ "Republic Act No. 6471". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. 4 August 1949. Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ "Kapuso stars portray heroes in GMA's cinematic version of the National Anthem". Philippine Entertainment Portal. 21 August 2010. Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ Amadís, Ma. Guerrero (14 August 2015). "Manuel L. Quezon is the subject of a new musical". Inquirer Lifestyle. Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ "Benjamin Alves wants to play Quezon again in 'Heneral Luna' sequels". GMA News Online (in Filipino). Philippine Entertainment Portal. 12 October 2015. Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ^ Deveza, Reyma (25 August 2018). "Benjamin Alves to play Manuel L. Quezon in upcoming movie". ABS-CBN News. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ^ "'Quezon's Game' named Best Foreign Movie in Texas fest". Manila Standard. 23 April 2019. Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ^ "Sound file" (MP3). Quezon.ph. Archived from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ "Talumpati: Manuel L. Quezon". Filipinolibrarian.blogspot.com. Archived from the original on 7 August 2010. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

Bibliography

[edit]- MacArthur, Douglas (1964). Reminiscences. McGraw-Hill.

- Quezon, Manuel Luis (1974). The Good Fight. AMS Press. ISBN 978-0-404-09036-4.

- Perret, Geoffrey (1996). Old Soldiers Never Die: The Life of Douglas MacArthur. Random House. ISBN 9780679428824.

External links

[edit]- Bonnie Harris, Cantor Joseph Cysner: From Zbaszyn to Manila.

- Online E-book of Future of the Philippines : interviews with Manuel Quezon by Edward Price Bell, The Chicago Daily News Co., 1925

- Online E-book of Discursos del Manuel L. Quezon, comissionado residente de Filipinas, pronunciados en la cámara de representantes de la discusión del Bill Jones (26, Septiembre-14, Octubre, 1914), published in Manila, 1915

- United States Congress. "Manuel L. Quezon (id: Q000009)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Manuel L. Quezon on the Presidential Museum and Library Archived 26 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- The Good Fight, autobiography, published 1946

- Newspaper clippings about Manuel L. Quezon in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- Manuel L. Quezon

- 1878 births

- 1944 deaths

- 20th-century deaths from tuberculosis

- Burials at Arlington National Cemetery

- Filipino city founders

- Colegio de San Juan de Letran alumni

- Exiled politicians

- Filipino exiles

- Filipino expatriates in the United States

- Filipino military leaders

- Filipino people of Spanish descent

- Filipino people of Chinese descent

- Filipino politicians of Chinese descent

- Filipino revolutionaries

- Governors of Quezon

- Hispanic and Latino American members of the United States Congress

- History of the Philippines (1898–1946)

- Tuberculosis deaths in New York (state)

- Majority leaders of the House of Representatives of the Philippines

- Members of the House of Representatives of the Philippines from Quezon

- Members of the United States Congress of Filipino descent

- Members of the United States House of Representatives of Asian descent

- Military history of the Philippines during World War II

- Nacionalista Party politicians

- People from Aurora (province)

- Candidates in the 1935 Philippine presidential election

- Candidates in the 1941 Philippine presidential election

- Knights Grand Cross of the Royal Order of Cambodia

- Officers of the Legion of Honour

- 19th-century Roman Catholics

- 20th-century Roman Catholics

- Filipino Roman Catholics

- People from Quezon

- People from Saranac Lake, New York

- People of the Philippine Revolution

- People of the Philippine–American War

- People who rescued Jews during the Holocaust

- Presidents of the Nacionalista Party

- Presidents of the Philippines

- Presidents of the Senate of the Philippines

- Quezon family

- Resident commissioners of the Philippines

- Secretaries of education of the Philippines

- Secretaries of national defense of the Philippines

- Senators of the 5th Philippine Legislature

- Senators of the 6th Philippine Legislature

- Senators of the 7th Philippine Legislature

- Senators of the 8th Philippine Legislature

- Senators of the 9th Philippine Legislature

- Senators of the 10th Philippine Legislature

- Tagalog people

- University of Santo Tomas alumni

- World War II political leaders

- Filipino independence activists

- 20th-century presidents in Asia

- Members of the Senate of the Philippines from the 5th district