Unix

| |

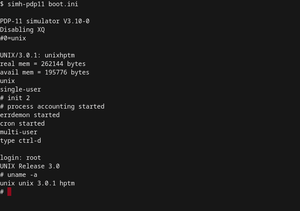

Unix System III running on a PDP-11 simulator | |

| Developer | Ken Thompson, Dennis Ritchie, Brian Kernighan, Douglas McIlroy, and Joe Ossanna at Bell Labs |

|---|---|

| Written in | C and assembly language |

| OS family | Unix |

| Source model | Historically proprietary software, while some Unix projects (including BSD family and illumos) are open-source |

| Initial release | Development started in 1969 First manual published internally in November 1971[1] Announced outside Bell Labs in October 1973[2] |

| Available in | English |

| Kernel type | Varies; monolithic, microkernel, hybrid |

| Influenced by | CTSS,[3] Multics |

| Default user interface | Command-line interface and Graphical (Wayland and X Window System; Android SurfaceFlinger; macOS Quartz) |

| License | Varies; some versions are proprietary, others are free/libre or open-source software |

| Official website | www |

| Internet history timeline |

|

Early research and development:

Merging the networks and creating the Internet:

Commercialization, privatization, broader access leads to the modern Internet:

Examples of Internet services:

|

Unix (/ˈjuːnɪks/ ⓘ, YOO-niks; trademarked as UNIX) is a family of multitasking, multi-user computer operating systems that derive from the original AT&T Unix, whose development started in 1969[1] at the Bell Labs research center by Ken Thompson, Dennis Ritchie, and others.[4] Initially intended for use inside the Bell System, AT&T licensed Unix to outside parties in the late 1970s, leading to a variety of both academic and commercial Unix variants from vendors including University of California, Berkeley (BSD), Microsoft (Xenix), Sun Microsystems (SunOS/Solaris), HP/HPE (HP-UX), and IBM (AIX).

The early versions of Unix—which are retrospectively referred to as "Research Unix"—ran on computers like the PDP-11 and VAX; Unix was commonly used on minicomputers and mainframes from the 1970s onwards.[5] It distinguished itself from its predecessors as the first portable operating system: almost the entire operating system is written in the C programming language (in 1973), which allows Unix to operate on numerous platforms.[6] Unix systems are characterized by a modular design that is sometimes called the "Unix philosophy". According to this philosophy, the operating system should provide a set of simple tools, each of which performs a limited, well-defined function.[7] A unified and inode-based filesystem and an inter-process communication mechanism known as "pipes" serve as the main means of communication,[4] and a shell scripting and command language (the Unix shell) is used to combine the tools to perform complex workflows.

Version 7 in 1979 was the final widely released Research Unix, after which AT&T sold UNIX System III, based on Version 7, commercially in 1982; to avoid confusion between the Unix variants, AT&T combined various versions developed by others and released it as UNIX System V in 1983. However as these were closed-source, the University of California, Berkeley continued developing BSD as an alternative. Other vendors that were beginning to create commercialized versions of Unix would base their version on either System V (like Silicon Graphics's IRIX) or BSD (like SunOS). Amid the "Unix wars" of standardization, AT&T alongside Sun merged System V, BSD, SunOS and Xenix, soldifying their features into one package as UNIX System V Release 4 (SVR4) in 1989, and it was commercialized by Unix System Laboratories, an AT&T spinoff.[8][9] A rival Unix by other vendors was released as OSF/1, however most commercial Unix vendors eventually changed their distributions to be based on SVR4 with BSD features added on top.

AT&T sold Unix to Novell in 1992, who later sold the UNIX trademark to a new industry consortium called The Open Group which allow the use of the mark for certified operating systems that comply with the Single UNIX Specification (SUS). Since the 1990s, Unix systems have appeared on home-class computers: BSD/OS was the first to be commercialized for i386 computers and since then free Unix-like clones of existing systems have been developed, such as FreeBSD and the combination of Linux and GNU, the latter of which have since eclipsed Unix in popularity. Unix has been, until 2005, the most widely used server operating system.[10] However in the present day, Unix distributions like IBM AIX, Oracle Solaris and OpenServer continue to be widely used in certain fields.[11][12]

Overview

[edit]

Unix was originally meant to be a convenient platform for programmers developing software to be run on it and on other systems, rather than for non-programmers.[13][14][15] The system grew larger as the operating system started spreading in academic circles, and as users added their own tools to the system and shared them with colleagues.[16]

At first, Unix was not designed to support multi-tasking[17] or to be portable.[6] Later, Unix gradually gained multi-tasking and multi-user capabilities in a time-sharing configuration, as well as portability. Unix systems are characterized by various concepts: the use of plain text for storing data; a hierarchical file system; treating devices and certain types of inter-process communication (IPC) as files; and the use of a large number of software tools, small programs that can be strung together through a command-line interpreter using pipes, as opposed to using a single monolithic program that includes all of the same functionality. These concepts are collectively known as the "Unix philosophy". Brian Kernighan and Rob Pike summarize this in The Unix Programming Environment as "the idea that the power of a system comes more from the relationships among programs than from the programs themselves".[18]

By the early 1980s, users began seeing Unix as a potential universal operating system, suitable for computers of all sizes.[19][20] The Unix environment and the client–server program model were essential elements in the development of the Internet and the reshaping of computing as centered in networks rather than in individual computers.

Both Unix and the C programming language were developed by AT&T and distributed to government and academic institutions, which led to both being ported to a wider variety of machine families than any other operating system.

The Unix operating system consists of many libraries and utilities along with the master control program, the kernel. The kernel provides services to start and stop programs, handles the file system and other common "low-level" tasks that most programs share, and schedules access to avoid conflicts when programs try to access the same resource or device simultaneously. To mediate such access, the kernel has special rights, reflected in the distinction of kernel space from user space, the latter being a lower priority realm where most application programs operate.

History

[edit]The origins of Unix date back to the mid-1960s when the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Bell Labs, and General Electric were developing Multics, a time-sharing operating system for the GE 645 mainframe computer.[21] Multics featured several innovations, but also presented severe problems. Frustrated by the size and complexity of Multics, but not by its goals, individual researchers at Bell Labs started withdrawing from the project. The last to leave were Ken Thompson, Dennis Ritchie, Douglas McIlroy, and Joe Ossanna,[17] who decided to reimplement their experiences in a new project of smaller scale. This new operating system was initially without organizational backing, and also without a name.

The new operating system was a single-tasking system.[17] In 1970, the group coined the name Unics for Uniplexed Information and Computing Service as a pun on Multics, which stood for Multiplexed Information and Computer Services. Brian Kernighan takes credit for the idea, but adds that "no one can remember" the origin of the final spelling Unix.[22] Dennis Ritchie,[17] Doug McIlroy,[1] and Peter G. Neumann[23] also credit Kernighan.

The operating system was originally written in assembly language, but in 1973, Version 4 Unix was rewritten in C. Ken Thompson faced multiple challenges attempting the kernel port due to the evolving state of C, which lacked key features like structures at the time.[17][24] Version 4 Unix, however, still had much PDP-11 specific code, and was not suitable for porting. The first port to another platform was a port of Version 6, made four years later (1977) at the University of Wollongong for the Interdata 7/32,[25] followed by a Bell Labs port of Version 7 to the Interdata 8/32 during 1977 and 1978.[26]

Bell Labs produced several versions of Unix that are collectively referred to as Research Unix. In 1975, the first source license for UNIX was sold to Donald B. Gillies at the University of Illinois Urbana–Champaign (UIUC) Department of Computer Science.[27]

During the late 1970s and early 1980s, the influence of Unix in academic circles led to large-scale adoption of Unix (BSD and System V) by commercial startups, which in turn led to Unix fragmenting into multiple, similar — but often slightly and mutually incompatible — systems including DYNIX, HP-UX, SunOS/Solaris, AIX, and Xenix. In the late 1980s, AT&T Unix System Laboratories and Sun Microsystems developed System V Release 4 (SVR4), which was subsequently adopted by many commercial Unix vendors.

In the 1990s, Unix and Unix-like systems grew in popularity and became the operating system of choice for over 90% of the world's top 500 fastest supercomputers,[28] as BSD and Linux distributions were developed through collaboration by a worldwide network of programmers. In 2000, Apple released Darwin, also a Unix system, which became the core of the Mac OS X operating system, later renamed macOS.[29]

Unix-like operating systems are widely used in modern servers, workstations, and mobile devices.[30]

Standards

[edit]

In the late 1980s, an open operating system standardization effort now known as POSIX provided a common baseline for all operating systems; IEEE based POSIX around the common structure of the major competing variants of the Unix system, publishing the first POSIX standard in 1988. In the early 1990s, a separate but very similar effort was started by an industry consortium, the Common Open Software Environment (COSE) initiative, which eventually became the Single UNIX Specification (SUS) administered by The Open Group. Starting in 1998, the Open Group and IEEE started the Austin Group, to provide a common definition of POSIX and the Single UNIX Specification, which, by 2008, had become the Open Group Base Specification.

In 1999, in an effort towards compatibility, several Unix system vendors agreed on SVR4's Executable and Linkable Format (ELF) as the standard for binary and object code files. The common format allows substantial binary compatibility among different Unix systems operating on the same CPU architecture.

The Filesystem Hierarchy Standard was created to provide a reference directory layout for Unix-like operating systems; it has mainly been used in Linux.

Components

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2023) |

The Unix system is composed of several components that were originally packaged together. By including the development environment, libraries, documents and the portable, modifiable source code for all of these components, in addition to the kernel of an operating system, Unix was a self-contained software system. This was one of the key reasons it emerged as an important teaching and learning tool and has had a broad influence. See § Impact, below.

The inclusion of these components did not make the system large – the original V7 UNIX distribution, consisting of copies of all of the compiled binaries plus all of the source code and documentation occupied less than 10 MB and arrived on a single nine-track magnetic tape, earning its reputation as a portable system.[31] The printed documentation, typeset from the online sources, was contained in two volumes.

The names and filesystem locations of the Unix components have changed substantially across the history of the system. Nonetheless, the V7 implementation has the canonical early structure:

- Kernel – source code in /usr/sys, composed of several sub-components:

- conf – configuration and machine-dependent parts, including boot code

- dev – device drivers for control of hardware (and some pseudo-hardware)

- sys – operating system "kernel", handling memory management, process scheduling, system calls, etc.

- h – header files, defining key structures within the system and important system-specific invariables

- Development environment – early versions of Unix contained a development environment sufficient to recreate the entire system from source code:

- ed – text editor, for creating source code files

- cc – C language compiler (first appeared in V3 Unix)

- as – machine-language assembler for the machine

- ld – linker, for combining object files

- lib – object-code libraries (installed in /lib or /usr/lib). libc, the system library with C run-time support, was the primary library, but there have always been additional libraries for things such as mathematical functions (libm) or database access. V7 Unix introduced the first version of the modern "Standard I/O" library stdio as part of the system library. Later implementations increased the number of libraries significantly.

- make – build manager (introduced in PWB/UNIX), for effectively automating the build process

- include – header files for software development, defining standard interfaces and system invariants

- Other languages – V7 Unix contained a Fortran-77 compiler, a programmable arbitrary-precision calculator (bc, dc), and the awk scripting language; later versions and implementations contain many other language compilers and toolsets. Early BSD releases included Pascal tools, and many modern Unix systems also include the GNU Compiler Collection as well as or instead of a proprietary compiler system.

- Other tools – including an object-code archive manager (ar), symbol-table lister (nm), compiler-development tools (e.g. lex & yacc), and debugging tools.

- Commands – Unix makes little distinction between commands (user-level programs) for system operation and maintenance (e.g. cron), commands of general utility (e.g. grep), and more general-purpose applications such as the text formatting and typesetting package. Nonetheless, some major categories are:

- sh – the "shell" programmable command-line interpreter, the primary user interface on Unix before window systems appeared, and even afterward (within a "command window").

- Utilities – the core toolkit of the Unix command set, including cp, ls, grep, find and many others. Subcategories include:

- Document formatting – Unix systems were used from the outset for document preparation and typesetting systems, and included many related programs such as nroff, troff, tbl, eqn, refer, and pic. Some modern Unix systems also include packages such as TeX and Ghostscript.

- Graphics – the plot subsystem provided facilities for producing simple vector plots in a device-independent format, with device-specific interpreters to display such files. Modern Unix systems also generally include X11 as a standard windowing system and GUI, and many support OpenGL.

- Communications – early Unix systems contained no inter-system communication, but did include the inter-user communication programs mail and write. V7 introduced the early inter-system communication system UUCP, and systems beginning with BSD release 4.1c included TCP/IP utilities.

- Documentation – Unix was one of the first operating systems to include all of its documentation online in machine-readable form.[32] The documentation included:

- man – manual pages for each command, library component, system call, header file, etc.

- doc – longer documents detailing major subsystems, such as the C language and troff

Impact

[edit]

The Unix system had a significant impact on other operating systems. It achieved its reputation by its interactivity, by providing the software at a nominal fee for educational use, by running on inexpensive hardware, and by being easy to adapt and move to different machines. Unix was originally written in assembly language, but was soon rewritten in C, a high-level programming language.[33] Although this followed the lead of CTSS, Multics and Burroughs MCP, it was Unix that popularized the idea.

Unix had a drastically simplified file model compared to many contemporary operating systems: treating all kinds of files as simple byte arrays. The file system hierarchy contained machine services and devices (such as printers, terminals, or disk drives), providing a uniform interface, but at the expense of occasionally requiring additional mechanisms such as ioctl and mode flags to access features of the hardware that did not fit the simple "stream of bytes" model. The Plan 9 operating system pushed this model even further and eliminated the need for additional mechanisms.

Unix also popularized the hierarchical file system with arbitrarily nested subdirectories, originally introduced by Multics. Other common operating systems of the era had ways to divide a storage device into multiple directories or sections, but they had a fixed number of levels, often only one level. Several major proprietary operating systems eventually added recursive subdirectory capabilities also patterned after Multics. DEC's RSX-11M's "group, user" hierarchy evolved into OpenVMS directories, CP/M's volumes evolved into MS-DOS 2.0+ subdirectories, and HP's MPE group.account hierarchy and IBM's SSP and OS/400 library systems were folded into broader POSIX file systems.

Making the command interpreter an ordinary user-level program, with additional commands provided as separate programs, was another Multics innovation popularized by Unix. The Unix shell used the same language for interactive commands as for scripting (shell scripts – there was no separate job control language like IBM's JCL). Since the shell and OS commands were "just another program", the user could choose (or even write) their own shell. New commands could be added without changing the shell itself. Unix's innovative command-line syntax for creating modular chains of producer-consumer processes (pipelines) made a powerful programming paradigm (coroutines) widely available. Many later command-line interpreters have been inspired by the Unix shell.

A fundamental simplifying assumption of Unix was its focus on newline-delimited text for nearly all file formats. There were no "binary" editors in the original version of Unix – the entire system was configured using textual shell command scripts. The common denominator in the I/O system was the byte – unlike "record-based" file systems. The focus on text for representing nearly everything made Unix pipes especially useful and encouraged the development of simple, general tools that could easily be combined to perform more complicated ad hoc tasks. The focus on text and bytes made the system far more scalable and portable than other systems. Over time, text-based applications have also proven popular in application areas, such as printing languages (PostScript, ODF), and at the application layer of the Internet protocols, e.g., FTP, SMTP, HTTP, SOAP, and SIP.

Unix popularized a syntax for regular expressions that found widespread use. The Unix programming interface became the basis for a widely implemented operating system interface standard (POSIX, see above). The C programming language soon spread beyond Unix, and is now ubiquitous in systems and applications programming.

Early Unix developers were important in bringing the concepts of modularity and reusability into software engineering practice, spawning a "software tools" movement. Over time, the leading developers of Unix (and programs that ran on it) established a set of cultural norms for developing software, norms which became as important and influential as the technology of Unix itself; this has been termed the Unix philosophy.

The TCP/IP networking protocols were quickly implemented on the Unix versions widely used on relatively inexpensive computers, which contributed to the Internet explosion of worldwide, real-time connectivity and formed the basis for implementations on many other platforms.

The Unix policy of extensive on-line documentation and (for many years) ready access to all system source code raised programmer expectations, and contributed to the launch of the free software movement in 1983.

Free Unix and Unix-like variants

[edit]In 1983, Richard Stallman announced the GNU (short for "GNU's Not Unix") project, an ambitious effort to create a free software Unix-like system—"free" in the sense that everyone who received a copy would be free to use, study, modify, and redistribute it. The GNU project's own kernel development project, GNU Hurd, had not yet produced a working kernel, but in 1991 Linus Torvalds released the Linux kernel as free software under the GNU General Public License. In addition to their use in the GNU operating system, many GNU packages – such as the GNU Compiler Collection (and the rest of the GNU toolchain), the GNU C library and the GNU Core Utilities – have gone on to play central roles in other free Unix systems as well.

Linux distributions, consisting of the Linux kernel and large collections of compatible software have become popular both with individual users and in business. Popular distributions include Red Hat Enterprise Linux, Fedora, SUSE Linux Enterprise, openSUSE, Debian, Ubuntu, Linux Mint, Slackware Linux, Arch Linux and Gentoo.[34]

A free derivative of BSD Unix, 386BSD, was released in 1992 and led to the NetBSD and FreeBSD projects. With the 1994 settlement of a lawsuit brought against the University of California and Berkeley Software Design Inc. (USL v. BSDi) by Unix System Laboratories, it was clarified that Berkeley had the right to distribute BSD Unix for free if it so desired. Since then, BSD Unix has been developed in several different product branches, including OpenBSD and DragonFly BSD.

Because of the modular design of the Unix model, sharing components is relatively common: most or all Unix and Unix-like systems include at least some BSD code, while some include GNU utilities in their distributions. Linux and BSD Unix are increasingly filling market needs traditionally served by proprietary Unix operating systems, expanding into new markets such as the consumer desktop, mobile devices and embedded devices.

In a 1999 interview, Dennis Ritchie voiced his opinion that Linux and BSD Unix operating systems are a continuation of the basis of the Unix design and are derivatives of Unix:[35]

I think the Linux phenomenon is quite delightful, because it draws so strongly on the basis that Unix provided. Linux seems to be among the healthiest of the direct Unix derivatives, though there are also the various BSD systems as well as the more official offerings from the workstation and mainframe manufacturers.

In the same interview, he states that he views both Unix and Linux as "the continuation of ideas that were started by Ken and me and many others, many years ago".[35]

OpenSolaris was the free software counterpart to Solaris developed by Sun Microsystems, which included a CDDL-licensed kernel and a primarily GNU userland. However, Oracle discontinued the project upon their acquisition of Sun, which prompted a group of former Sun employees and members of the OpenSolaris community to fork OpenSolaris into the illumos kernel. As of 2014, illumos remains the only active, open-source System V derivative.

ARPANET

[edit]In May 1975, RFC 681 described the development of Network Unix by the Center for Advanced Computation at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.[36] The Unix system was said to "present several interesting capabilities as an ARPANET mini-host". At the time, Unix required a license from Bell Telephone Laboratories that cost US$20,000 for non-university institutions, while universities could obtain a license for a nominal fee of $150. It was noted that Bell was "open to suggestions" for an ARPANET-wide license.

The RFC specifically mentions that Unix "offers powerful local processing facilities in terms of user programs, several compilers, an editor based on QED, a versatile document preparation system, and an efficient file system featuring sophisticated access control, mountable and de-mountable volumes, and a unified treatment of peripherals as special files." The latter permitted the Network Control Program (NCP) to be integrated within the Unix file system, treating network connections as special files that could be accessed through standard Unix I/O calls, which included the added benefit of closing all connections on program exit, should the user neglect to do so. In order "to minimize the amount of code added to the basic Unix kernel", much of the NCP code ran in a swappable user process, running only when needed.[36]

Branding

[edit]

AT&T did not allow licensees to use the Unix name; thus Microsoft called its variant Xenix, for example.[37] In October 1993, Novell, the company that owned the rights to the Unix System V source at the time, transferred the trademarks of Unix to the X/Open Company (now The Open Group),[38] and in 1995 sold the related business operations to Santa Cruz Operation (SCO).[39][40] Whether Novell also sold the copyrights to the actual software was the subject of a federal lawsuit in 2006, SCO v. Novell, which Novell won. The case was appealed, but on August 30, 2011, the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit affirmed the trial decisions, closing the case.[41] Unix vendor SCO Group Inc. accused Novell of slander of title.

The present owner of the trademark UNIX is The Open Group, an industry standards consortium. Only systems fully compliant with and certified to the Single UNIX Specification qualify as "UNIX" (others are called "Unix-like").

By decree of The Open Group, the term "UNIX" refers more to a class of operating systems than to a specific implementation of an operating system; those operating systems which meet The Open Group's Single UNIX Specification should be able to bear the UNIX 98 or UNIX 03 trademarks today, after the operating system's vendor pays a substantial certification fee and annual trademark royalties to The Open Group.[42] Systems that have been licensed to use the UNIX trademark include AIX,[43] EulerOS,[44] HP-UX,[45] Inspur K-UX,[46] IRIX,[47] macOS,[48] Solaris,[49] Tru64 UNIX (formerly "Digital UNIX", or OSF/1),[50] and z/OS.[51] Notably, EulerOS and Inspur K-UX are Linux distributions certified as UNIX 03 compliant.[52][53]

Sometimes a representation like Un*x, *NIX, or *N?X is used to indicate all operating systems similar to Unix. This comes from the use of the asterisk (*) and the question mark characters as wildcard indicators in many utilities. This notation is also used to describe other Unix-like systems that have not met the requirements for UNIX branding from the Open Group.

The Open Group requests that UNIX always be used as an adjective followed by a generic term such as system to help avoid the creation of a genericized trademark.

Unix was the original formatting,[disputed – discuss] but the usage of UNIX remains widespread because it was once typeset in small caps (Unix). According to Dennis Ritchie, when presenting the original Unix paper to the third Operating Systems Symposium of the American Association for Computing Machinery (ACM), "we had a new typesetter and troff had just been invented and we were intoxicated by being able to produce small caps".[54] Many of the operating system's predecessors and contemporaries used all-uppercase lettering, so many people wrote the name in upper case due to force of habit. It is not an acronym.[55]

Trademark names can be registered by different entities in different countries and trademark laws in some countries allow the same trademark name to be controlled by two different entities if each entity uses the trademark in easily distinguishable categories. The result is that Unix has been used as a brand name for various products including bookshelves, ink pens, bottled glue, diapers, hair driers and food containers.[56]

Several plural forms of Unix are used casually to refer to multiple brands of Unix and Unix-like systems. Most common is the conventional Unixes, but Unices, treating Unix as a Latin noun of the third declension, is also popular. The pseudo-Anglo-Saxon plural form Unixen is not common, although occasionally seen. Sun Microsystems, developer of the Solaris variant, has asserted that the term Unix is itself plural, referencing its many implementations.[57]

See also

[edit]- Comparison of operating systems and free and proprietary software

- List of operating systems, Unix systems, and Unix commands

- Plan 9 from Bell Labs

- Timeline of operating systems

- Unix time

- Market share of operating systems

- Year 2038 problem

References

[edit]- ^ a b c McIlroy, M. D. (1987). A Research Unix reader: annotated excerpts from the Programmer's Manual, 1971–1986 (PDF) (Technical report). CSTR. Bell Labs. 139. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 November 2017.

- ^ Ritchie, D. M.; Thompson, K. (1974). "The UNIX Time-Sharing System" (PDF). Communications of the ACM. 17 (7): 365–375. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.118.1214. doi:10.1145/361011.361061. S2CID 53235982. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 June 2015.

- ^ Ritchie, Dennis M. (1977). The Unix Time-sharing System: A retrospective (PDF). Tenth Hawaii International Conference on the System Sciences. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 11, 2015. Retrieved September 26, 2024.

a good case can be made that [UNIX] is in essence a modern implementation of MIT's CTSS system

- ^ a b Ritchie, D.M.; Thompson, K. (July 1978). "The UNIX Time-Sharing System". Bell System Tech. J. 57 (6): 1905–1929. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.112.595. doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1978.tb02136.x. Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- ^ Schwartz, John (June 11, 2000). "Microsoft's Next Trials". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 13, 2024. Retrieved December 17, 2024.

- ^ a b Ritchie, Dennis M. (January 1993). "The Development of the C Language" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 June 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Raymond, Eric (19 September 2003). The Art of Unix Programming. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-13-142901-7. Archived from the original on 12 February 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ^ Computerworld, GARY ANTHES of; IDG (July 27, 2009). "Timeline - 40 Years Of Unix - NYTimes.com". archive.nytimes.com. Retrieved December 4, 2024.

- ^ Lewis, Peter H. (June 12, 1988). "Is Unix's Time Finally at hand?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 5, 2011. Retrieved December 17, 2024.

- ^ Bangeman, Eric (February 22, 2006). "Windows passes Unix in server sales". Ars Technica. Retrieved December 5, 2024.

- ^ Garvin, Skip (September 19, 2019). "Top IBM Power Systems myths: "IBM AIX is dead and Unix isn't relevant in today's market" (part 2)". IBM Blog. Retrieved December 5, 2024.

- ^ "Unix is dead. Long live Unix!".

- ^ Raymond, Eric Steven (2003). "The Elements of Operating-System Style". The Art of Unix Programming. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- ^ Brand, Stewart (1984). Tandy/Radio Shack Book: Whole Earth Software Catalog. Quantum Press/Doubleday. ISBN 9780385191661.

UNIX was created by software developers for software developers, to give themselves an environment they could completely manipulate.

- ^ Spolsky, Joel (December 14, 2003). "Biculturalism". Joel on Software. Retrieved March 21, 2021.

When Unix was created and when it formed its cultural values, there were no end users.

- ^ Powers, Shelley; Peek, Jerry; O'Reilly, Tim; Loukides, Mike (2002). Unix Power Tools. "O'Reilly Media, Inc.". ISBN 978-0-596-00330-2.

- ^ a b c d e Ritchie, Dennis M. "The Evolution of the Unix Time-sharing System" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 April 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- ^ Kernighan, Brian W. Pike, Rob. The UNIX Programming Environment. 1984. viii

- ^ Fiedler, Ryan (October 1983). "The Unix Tutorial / Part 3: Unix in the Microcomputer Marketplace". BYTE. p. 132. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- ^ Brand, Stewart (1984). Tandy/Radio Shack Book: Whole Earth Software Catalog. Quantum Press/Doubleday. ISBN 9780385191661.

The best thing about UNIX is its portability. UNIX ports across a full range of hardware—from the single-user $5000 IBM PC to the $5 million Cray. For the first time, the point of stability becomes the software environment, not the hardware architecture; UNIX transcends changes in hardware technology, so programs written for the UNIX environment can move into the next generation of hardware.

- ^ Stuart, Brian L. (2009). Principles of operating systems: design & applications. Boston, Massachusetts: Thompson Learning. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-4188-3769-3.

- ^ Dolya, Aleksey (29 July 2003). "Interview with Brian Kernighan". Linux Journal. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017.

- ^ Rik Farrow. "An Interview with Peter G. Neumann" (PDF). ;login:. 42 (4): 38.

That then led to Unics (the castrated one-user Multics, so- called due to Brian Kernighan) later becoming UNIX (probably as a result of AT&T lawyers).

- ^ Georgiadis, Evangelos (2024). "Letter to the Editor". Communications of the ACM. 67. doi:10.1145/3654698. ISSN 0001-0782.

- ^ Reinfelds, Juris. "The First Port of UNIX" (PDF). Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ "Portability of C Programs and the UNIX System". Bell-labs.com. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ^ Thompson, Ken (16 September 2014). "personal communication, Ken Thompson to Donald W. Gillies". UBC ECE website. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016.

- ^ "Operating system Family - Systems share". Top 500 project.

- ^ "Loading". Apple Developer. Archived from the original on 9 June 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ "Unix's Revenge". asymco. 29 September 2010. Archived from the original on 9 November 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ "Unix: the operating system setting new standards". IONOS Digitalguide. May 29, 2020. Retrieved May 10, 2022.

- ^ Shelley Powers; Jerry Peek; Tim O'Reilly; Michael Kosta Loukides; Mike Loukides (2003). Unix Power Tools. "O'Reilly Media, Inc.". p. 32. ISBN 978-0-596-00330-2. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ Ritchie, Dennis (1979). "The Evolution of the Unix Time-sharing System". Bell Labs. Archived from the original on 11 June 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

Perhaps the most important watershed occurred during 1973, when the operating system kernel was rewritten in C.

- ^ "Major Distributions". distrowatch.com.

- ^ a b Benet, Manuel (1999). "Interview With Dennis M. Ritchie". LinuxFocus.org. Archived from the original on 4 January 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ a b Holmgren, Steve (May 1975). Network Unix. IETF. doi:10.17487/RFC0681. RFC 681. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ^ Libes, Sol (November 1982). "Bytelines". BYTE. pp. 540–547.

- ^ Chuck Karish (October 12, 1993). "The name UNIX is now the property of X/Open". Newsgroup: comp.std.unix. Usenet: 29hug3INN4qt@rodan.UU.NET. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ "Novell Completes Sale of UnixWare Business to The Santa Cruz Operation | Micro Focus". www.novell.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ^ "HP, Novell and SCO To Deliver High-Volume UNIX OS With Advanced Network And Enterprise Services". Novell.com. September 20, 1995. Archived from the original on January 23, 2007. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ^ Jones, Pamela. "SCO Files Docketing Statement and We Find Out What Its Appeal Will Be About". Groklaw. Groklaw.net. Retrieved April 12, 2011.

- ^ The Open Group. "The Open Brand Fee Schedule". Archived from the original on December 31, 2011. Retrieved December 26, 2011.

The right to use the UNIX Trademark requires the Licensee to pay to The Open Group an additional annual fee, calculated in accordance with the fee table set out below.

- ^ The Open Group. "AIX 6 Operating System V6.1.2 with SP1 or later certification". Archived from the original on April 8, 2016.

- ^ The Open Group (September 8, 2016). "Huawei EulerOS 2.0 certification".

- ^ The Open Group. "HP-UX 11i V3 Release B.11.31 or later certification". Archived from the original on April 8, 2016.

- ^ The Open Group. "Inspur K-UX 2.0 certification". Archived from the original on July 9, 2014.

- ^ The Open Group. "IRIX 6.5.28 with patches (4605 and 7029) certification". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- ^ "macOS version 10.12 Sierra on Intel-based Mac computers". The Open Group. Archived from the original on October 2, 2016.

- ^ The Open Group. "Oracle Solaris 11 FCS and later certification". Archived from the original on September 24, 2015.

- ^ Bonnie Talerico. "Hewlett-Packard Company Conformance Statement". The Open Group. Archived from the original on December 10, 2015. Retrieved December 8, 2015.

- ^ Vivian W. Morabito. "IBM Corporation Conformance Statement". The Open Group. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- ^ Peng Shen. "Huawei Conformance Statement". The Open Group. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

- ^ Peng Shen. "Huawei Conformance Statement: Commands and Utilities V4". The Open Group. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

- ^ Raymond, Eric S. (ed.). "Unix". The Jargon File. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ^ Troy, Douglas (1990). UNIX Systems. Computing Fundamentals. Benjamin/Cumming Publishing Company. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-201-19827-0.

- ^ "Autres Unix, autres moeurs (OtherUnix)". Bell Laboratories. April 1, 2000. Archived from the original on April 3, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ "History of Solaris" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 18, 2017.

UNIX is plural. It is not one operating system but, many implementations of an idea that originated in 1965.

Further reading

[edit]- General

- Ritchie, D.M.; Thompson, K. (July–August 1978). "The UNIX Time-Sharing System". Bell System Technical Journal. 57 (6). Archived from the original on November 3, 2010.

- "UNIX History". www.levenez.com. Retrieved March 17, 2005.

- "AIX, FreeBSD, HP-UX, Linux, Solaris, Tru64". UNIXguide.net. Retrieved March 17, 2005.

- "Linux Weekly News, February 21, 2002". lwn.net. Retrieved April 7, 2006.

- Lions, John: Lions' "Commentary on the Sixth Edition UNIX Operating System". with Source Code, Peer-to-Peer Communications, 1996; ISBN 1-57398-013-7

- Books

- Salus, Peter H.: A Quarter Century of UNIX, Addison Wesley, June 1, 1994; ISBN 0-201-54777-5

- Television

- Computer Chronicles (1985). "UNIX".

- Computer Chronicles (1989). "Unix".

- Talks

- Ken Thompson (2019). "VCF East 2019 -- Brian Kernighan interviews Ken Thompson" (Interview).

- Marshall Kirk McKusick (2006). History of the Berkeley Software Distributions (three one-hour lectures).

External links

[edit]- The UNIX Standard, at The Open Group.

- The Evolution of the Unix Time-sharing System at the Wayback Machine (archived April 8, 2015)

- The Creation of the UNIX Operating System at the Wayback Machine (archived April 2, 2014)

- The Unix Tree: files from historic releases

- Unix History Repository — a git repository representing a reconstructed version of the Unix history on GitHub

- The Unix 1st Edition Manual

- AT&T Tech Channel Archive: The UNIX Operating System: Making Computers More Productive (1982) on YouTube (film about Unix featuring Dennis Ritchie, Ken Thompson, Brian Kernighan, Alfred Aho, and more)

- AT&T Tech Channel Archive: The UNIX System: Making Computers Easier to Use (1982) on YouTube (complementary film to the preceding "Making Computers More Productive")

- audio bsdtalk170 - Marshall Kirk McKusick at DCBSDCon -- on history of tcp/ip (in BSD) -- abridgement of the three lectures on the history of BSD.

- A History of UNIX before Berkeley: UNIX Evolution: 1975-1984

- BYTE Magazine, September 1986: UNIX and the MC68000 – a software perspective on the MC68000 CPU architecture and UNIX compatibility