Tigard, Oregon

Tigard, Oregon | |

|---|---|

Main Street in Downtown | |

| Motto: A Place to Call Home | |

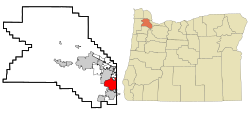

Location in Oregon | |

| Coordinates: 45°25′30″N 122°46′44″W / 45.42500°N 122.77889°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Oregon |

| County | Washington |

| Incorporated | 1961 |

| Area | |

• Total | 12.76 sq mi (33.04 km2) |

| • Land | 12.76 sq mi (33.03 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.01 km2) |

| Elevation | 240 ft (70 m) |

| Population | |

• Total | 54,539 |

| • Density | 4,275.89/sq mi (1,650.99/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (Pacific) |

| ZIP codes | 97223, 97224, 97281 |

| Area code(s) | 503 and 971 |

| FIPS code | 41-73650 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2412069[2] |

| Website | City of Tigard |

Tigard (/ˈtaɪɡərd/ ⓘ TY-gərd) is a city in Washington County, Oregon, United States. The population was 54,539 at the 2020 census, making it the 12th most populous city in Oregon. Incorporated in 1961, the city is located south of Beaverton and north of Tualatin, and is part of the Portland metropolitan area. Interstate 5 and Oregon Route 217 are the main freeways in the city, with Oregon Route 99W and Oregon Route 210 serving as other major highways. Public transit service is provided by TriMet, via several bus routes and the WES Commuter Rail line.

History

[edit]

Before colonization by European settlers, the Atfalati inhabited the Tualatin Valley in several hunter-gatherer villages including Chachimahiyuk ("Place of aromatic herbs"), near present-day Tigard. Primary food stuffs included deer, camas root, fish, berries, elk, and various nuts. To encourage the growth of the camas plant and maintain a habitat beneficial to deer and elk, the group regularly burned the valley floor to discourage the growth of forests, a common practice among the Kalapuya.[4] The Atfalati spoke the Tualatin-Yamhill (Northern Kalapuya) language, which was one of the three Kalapuyan languages. Prior to contact with white explorers, traders, and missionaries, the Kalapuya population is believed to have numbered as many as 15,000 people.[5]

Euro-Americans began arriving in the Atfalati's homeland in the early 19th century, and settlers in the 1840s.[4] As with the other Kalapuyan peoples, the arrival of Euro-Americans led to dramatic social disruptions.[6] By the 1830s, diseases had decimated the Atfalati.[4] The tribe had already experienced population decreased from smallpox epidemics in 1782 and 1783.[6] It is estimated that the band was reduced to a population of around 600 in 1842, and had shrunk to only 60 in 1848. These upheavals diminished the Atfalati's ability to challenge white encroachment.

Under the terms of a treaty of April 19, 1851, the Atfalatis ceded their lands in return for a small reservation at Wapato Lake as well as "money, clothing, blankets, tools, a few rifles, and a horse for each of their headmen--Kaicut, La Medicine, and Knolah."[6] At the time of the treaty, there were 65 Atfalatis.[6] The treaty resulted in the loss of much of the Atfalati's lands, but was preferable to removal east of the Cascade Mountains, which the government initially had demanded.[6] This treaty, however, was never ratified.[4][6] Under continuing pressure, the government and Kalapuya renegotiated a treaty with Oregon Superintendent of Indian Affairs Joel Palmer.[6] This treaty, the Treaty with the Kalapuya, etc. (also known as the Willamette Valley Treaty or Dayton Treaty) was signed January 4, 1855, and ratified by Congress, on March 3, 1855 (10 Stat. 1143).[6] Under the terms of the treaty, the indigenous peoples of the Willamette Valley agreed to remove to a reservation later designated by the federal government as the Grand Ronde reservation in the western part of the Willamette Valley at the foothills of the Oregon Coast Range, sixty miles south of their original homeland.[4][6]

The Donation Land Claim Act of 1850 promoted homestead settlement in the Oregon territory and encouraged thousands of white settlers to come to the area. Like many towns in the Willamette Valley, Tigard was settled by several families. The most noteworthy was the Tigard family, headed by Wilson M. Tigard. Arriving in the area known as "East Butte" in 1852, the family settled and became involved in organizing and building the East Butte School, a general store (which, starting in 1886, also housed the area's post office) and a meeting hall, and renamed East Butte to "Tigardville" in 1886.[7] The Evangelical organization built the Emanuel Evangelical Church at the foot of Bull Mountain, south of the Tigard store in 1886. A blacksmith shop was opened in the 1890s by John Gaarde across from the Tigard Store, and in 1896 a new E. Butte school was opened to handle the growth the community was experiencing from an incoming wave of German settlers.

The period between 1907 and 1910 marked a rapid acceleration in growth as Main Street blossomed with the construction of several new commercial buildings, Germania Hall (a two-story building featuring a restaurant, grocery store, dance hall, and rooms to rent), a shop/post office, and a livery stable. Limited telephone service began in 1908.

In 1910, the arrival of the Oregon Electric Railway triggered the development of Main Street and pushed Tigardville from being merely a small farming community into a period of growth which would lead to its incorporation as a city in 1961. The town was renamed Tigard in 1907 by the railroad to greater distinguish it from the nearby Wilsonville,[7] and the focus of the town reoriented northeast towards the new rail stop as growth accelerated.

1911 marked the introduction of electricity, as the Tualatin Valley Electric company joined Tigard to a service grid with Sherwood and Tualatin. William Ariss built a blacksmith shop on Main Street in 1912 that eventually evolved into a modern service station. In the 1930s the streets and walks of Main Street were finally paved, and another school established to accommodate growth.

The city was the respondent in (and eventual loser of) the landmark property rights case, Dolan v. City of Tigard, decided by the Supreme Court of the United States in 1994. The case established the "rough proportionality" test that is now applied throughout the United States when a local government evaluates a land use application and determines the exactions to require of the recipient of a land use approval.[8]

In the 2004 general elections, the city of Tigard won approval from its voters to annex the unincorporated suburbs on Bull Mountain, a hill to the west of Tigard. However, residents in that area have rejected annexation and are currently fighting in court various moves by the city.

Geography

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 11.69 square miles (30.28 km2), all land.[9]

Neighborhoods

[edit]

The city of Tigard is officially divided into 14 geographic areas around schools and major transportation routes. Each neighborhood has been assigned an area number that goes, 1–13. Except for the newest edition of River Terrace. [10] Some of the neighborhoods carry unofficial names long associated with them prior to their current numeric designations.[11]

• Bull Mountain - Area 12

Bull Mountain Park is in this area.

• Cook Park (South Tigard) - Area 9

Named after the park of the same name, Tigard High School is in this area.

• Derry Dell (Central Tigard) - Area 10

This area is south of the Jack Park neighborhoods, also bordering 99W.

• Downtown - Area 6

Tigard’s city hall is here, along with its revitalized downtown area.

• Durham Road - Area 7

Named after Durham Road, this area is located just north of the Cook Park/Area 9 neighborhoods & the city of Durham itself.

• Englewood Park - Area 2

Named after the nearby park park of the same name.

• Greenburg Road - Area 3

A historic area tied to Tigard’s early roots, The Washington Square Mall is in this area.

• Jack Park - Area 11

Tualatin Valley Fire & Rescue station 50 is located in this area.

• Metzger (North Tigard) - Area 4

The geographical area encompasses the entire area of the community.

• River Terrace

A 500-acre area on the city’s westernmost edge. With the completion of the River Terrace Community Plan in 2014, this area is Tigard’s newest neighborhood.

• (Scholls/Summerlake) - Area 1

This area borders on the Jack Park/Area 11 neighborhoods and Scholls Ferry Road.

• Southview - Area 8

A mostly residential area to the east of King City.

• Tigard Triangle - Area 5

This area forms a triangle due to the I-5, 99W & 217 highways intersecting.

• West Tigard - Area 13

This area encompasses the northwest slope of Bull Mountain.

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 6,499 | — | |

| 1980 | 14,799 | 127.7% | |

| 1990 | 29,344 | 98.3% | |

| 2000 | 42,249 | 44.0% | |

| 2010 | 48,035 | 13.7% | |

| 2020 | 54,539 | 13.5% | |

| 1961 estimated pop: 1084. Sources: 1961–2000,[12] 2010,[13] U.S. Decennial Census[14] 2018 Estimate[15] [3] | |||

North of McDonald Street, Tigard, along with Metzger and some of the unincorporated Bull Mountain area, uses the 97223 ZIP code for incoming mail, while the southern half of the city uses 97224, as do the nearby city of King City and the community of Durham. All mail for both ZIP codes is processed in Portland. The Tigard Post Office on Main Street has a ZIP code of 97281, which is used only for post office boxes. Local phone numbers may be within the 503 or 971 area codes.

2010 census

[edit]As of the census[16] of 2010, there were 48,035 people, 19,157 households, and 12,470 families residing in the city. The population density was 4,067.3 inhabitants per square mile (1,570.4/km2). There were 20,068 housing units at an average density of 1,699.2 per square mile (656.1/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 79.6% White, 1.8% African American, 0.7% Native American, 7.2% Asian, 0.9% Pacific Islander, 5.9% from other races, and 4.0% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 12.7% of the population.

There were 19,157 households, of which 33.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 50.4% were married couples living together, 10.0% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.6% had a male householder with no wife present, and 34.9% were non-families. 26.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.49 and the average family size was 3.04.

The median age in the city was 37.4 years. 24.1% of residents were under the age of 18; 8.1% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 29.2% were from 25 to 44; 27.4% were from 45 to 64; and 11.3% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 49.0% male and 51.0% female.

2000 census

[edit]As of the census of 2000, there were 41,223 people, 16,507 households, and 10,746 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,795.3 people per square mile (1,465.4 people/km2). There were 17,369 housing units at an average density of 1,599.1 per square mile (617.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 85.38% White, 5.57% Asian, 1.14% African American, 0.61% Native American, 0.53% Pacific Islander, 3.76% from other races, and 3.00% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 8.94% of the population. There were 16,507 households, out of which 33.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 52.0% were married couples living together, 9.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 34.9% were non-families. 26.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.48 and the average family size was 3.03.

In the city, the population dispersal was 25.5% under the age of 18, 9.0% from 18 to 24, 34.1% from 25 to 44, 21.4% from 45 to 64, and 10.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 96.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 92.8 males. The median income for a household in the city was $51,581, and the median income for a family was $61,656. Males had a median income of $44,597 versus $31,351 for females. The per capita income for the city was $25,110. About 5.0% of families and 6.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 7.8% of those under age 18 and 3.6% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

[edit]

Companies based in Tigard include Consumer Cellular, Gerber Legendary Blades, LaCie, NuScale Power, and Stash Tea Company, among others. The city is also home to the Washington Square mall, one of the largest in Oregon, and the northern part of Bridgeport Village. Medical Teams International is also based in Tigard.

| Employer | Employees (2014)[17] |

|---|---|

| 1. Capital One Services | 861 |

| 2. Tigard-Tualatin School District | 779 |

| 3. Nordstrom | 422 |

| 4. Macy's Department Stores | 404 |

| 5. Oregon Public Employees Retirement System | 396 |

| 6. Costco Wholesale | 273 |

| 7. City of Tigard | 257 |

| 8. Winco | 176 |

| 9. Albertson's | 174 |

Arts and culture

[edit]The John Tigard House, constructed by the son of Wilson M. Tigard in 1880 at the corner of SW Pacific Hwy. and SW Gaarde St., remains, having been saved from demolition in the 1970s by the Tigard Area Historical and Preservation Association. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979, and now stands at the corner of SW Canterbury Lane and SW 103rd St.

During the Portland Rose Festival every summer, the Tigard Festival of Balloons is held at Cook Park near Tigard High School.[18] The tallest building in both the city and county is a 12-story building at Lincoln Center.[19]

Broadway Rose Theatre Company is a professional musical theatre company based in Tigard. The company performs at their home theatre, The New Stage (located just west of downtown Tigard) and at Tigard High School during the summer months. It was founded in 1991 by Dan Murphy, Sharon Maroney and Tigard native Joseph Morkys. What began as a small summer stock theatre has grown into a large, nonprofit organization, and has received many regional theatre awards including several Drammys,[20] Portland Area Musical Theatre Awards[21] and BroadwayWorld Portland Awards.[22]

The Joy Cinema and Pub is a local independent theater that specializes in repertory screenings and cult films.[23]

Government

[edit]

Fire protection and EMS services are provided through Tualatin Valley Fire and Rescue.[24]

Past mayors

[edit]These people have served as mayor of the city.[citation needed]

- 1974–1984: Wilbur Bishop

- 1984: Ken Scheckla[P]

- 1984–1986: John E. Cook

- 1987–1988: Tom Brian

- 1989–1994: Gerald Edwards

- 1994: Jack Schwab

- 1994–2000: Jim Nicoli[D]

- 2001–2003: Jim Griffith[A][D]

- 2003–2012: Craig Dirksen[A]

- 2013–2018: John L. Cook

- 2019–2022: Jason Snider

- 2023-: Heidi Lueb

[A] Appointed to fill out term

[D] Died in office

[P] Mayor Pro tem

Education

[edit]

The city of Tigard falls mostly under the jurisdiction of the Tigard-Tualatin School District; however, some of the northwesternmost part of the city falls under the jurisdiction of the Beaverton School District.[25] The Tigard-Tualatin School District contains ten elementary schools, three middle schools and two high schools. Tigard is home to Tigard High School, Fowler Middle School, Twality Middle School, Alberta Rider Elementary, CF Tigard Elementary, Durham Elementary, Mary Woodward Elementary, Deer Creek Elementary, Metzger Elementary, and Templeton Elementary. The district also operates the alternative school Creekside Community High School.

Private schools include Gaarde Christian School,[26] Oregon Islamic Academy and Westside Christian High School. Higher education includes a branch of Everest Institute, a branch of the University of Phoenix, and a branch of National American University. The closest traditional four-year college is Lewis & Clark College in Portland. The city operates the Tigard Public Library, which started in 1963.[27]

From the 1980s until 1992 the Portland Japanese School, a weekend Japanese educational program for Japanese citizens and Japanese Americans, was held at Twality Middle School.[28]

Transportation

[edit]

Interstate 5 passes along the eastern edge of the city, with Oregon Route 217's southern terminus at I-5 at Tigard. Other major roads are Oregon Route 99W, Boones Ferry Road, and Hall Boulevard (Boones Ferry and Hall, along with a small portion of Durham Road, are the components of Oregon Route 141). Oregon Route 210 is located along the northern boundary, separating Tigard from Beaverton. Public transportation is provided by TriMet, with service via the 12, 43, 45, 62, 64, 76, 78, and 94 bus lines and the Westside Express Service (WES), a commuter rail line connecting to Wilsonville and Beaverton. WES has a stop at Tigard Transit Center, with Washington Square Transit Center as the only other TriMet transit center in the city. A proposed new light rail line, the Southwest Corridor light rail project, would have connected Tigard Transit Center to the MAX Green Line by 2027 had voters in November 2020 approved a measure to provide the region's share of the funding, but the measure did not pass.[29]

Notable people

[edit]- Margaret Bechard, writer

- Sammy Carlson, professional freestyle skier

- Kevin Duckworth, NBA professional basketball player

- Katherine Dunn, writer

- Mike Erickson, businessman and politician

- Johnny Frederick, professional baseball player

- Larry Galizio, politician

- Mike Kinkade, professional baseball player

- Kevin Kunnert, NBA professional basketball player, University of Iowa basketball player

- Owen Marecic, football player at Stanford University

- Kaitlin Olson, actress[30]

- Pat Whiting, politician

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Tigard, Oregon

- ^ a b "Census Population API". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Buan, Carolyn M. (1999). This Far-Off Sunset Land: A Pictorial History of Washington County, Oregon. Virginia Beach, VA: The Donning Company Publishers. pp. 17–22. ISBN 1-57864-037-7.

- ^ Robert T. Boyd, The Coming of the Spirit of Pestilence: Introduced Infectious Diseases and Population Decline among Northwest Coast Indians. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 1999; pp. 324–325, table 16. Cited in Melinda Marie Jetté, "'Beaver are Numerous but the Natives ... Will Not Hunt Them': Native-Fur Trader Relations in the Willamette Valley, 1812–1814," Pacific Northwest Quarterly, Winter 2006/07, pg. 3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ruby, Robert H. (2010). A Guide to the Indian Tribes of the Pacific Northwest. Oklahoma City, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806140247.

- ^ a b Sherman, Barbara (March 26, 2009). "Nearing the century mark, Curtis Tigard reflects on his namesake city". Portland Tribune. Pamplin Media Group. Archived from the original on January 31, 2015. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- ^ "Dolan v. Tigard".

- ^ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 25, 2012. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ^ "River Terrace". tigard-or.gov.

- ^ "Neighborhood Networks". Archived from the original on March 13, 2011. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- ^ "Tigard Community Profile: 2006 Edition" (PDF). City of Tigard. July 2006. p. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 2, 2007. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- ^ "2010 Census profiles: Oregon cities alphabetically T-Y" (PDF). Portland State University Population Research Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 22, 2012. Retrieved September 16, 2011.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved September 25, 2013.

- ^ "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ^ Bray, Kari (May 10, 2014). "Home values, average income, top employers and more: Tigard by the numbers". The Oregonian. Retrieved May 11, 2014.

- ^ "Tigard Festival of Balloons".

- ^ Allen, Martha. Tigard celebrates year of great growth, development. The Oregonian, December 29, 1987, West Zoner, p. C8.

- ^ "Past Winners". Drammy Awards. June 8, 2013. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- ^ "PAMTA". Oregon ArtsWatch. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- ^ Coverage, BWW Special. "2015 BroadwayWorld Portland Awards Winners Announced - THOROUGHLY MODERN MILLIE Wins Big!". BroadwayWorld.com. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- ^ "The Joy Cinema and Pub". The Joy Cinema and Pub. Retrieved March 25, 2023.

- ^ "About TVF&R". Tualatin Valley Fire & Rescue. Retrieved March 13, 2014.

- ^ "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Washington County, OR" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ^ "Gaarde Christian School". gaardechristian.com.

- ^ Nirappil, Fenit (October 26, 2013). "Tigard Public Library plans to celebrate 50th birthday". The Oregonian. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- ^ Florip, Eric. "Every weekend, Tualatin's Hazelbrook Middle School becomes Portland Japanese School, where it's all math and language" (Archive) The Oregonian. June 2, 2011. Retrieved on April 9, 2015.

- ^ Theen, Andrew (November 3, 2020). "Voters reject Metro's payroll tax to fund billions in transportation projects". The Oregonian. Archived from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved May 22, 2022.

- ^ Haynes, Dane (April 10, 2017). "Kaitlin Olson Turn Shining Star". Portland Tribune. Archived from the original on August 18, 2023. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Tigard, Oregon at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tigard, Oregon at Wikimedia Commons

- Entry for Tigard in the Oregon Blue Book

- Garvey, Sean. "Tigard". The Oregon Encyclopedia.

- A More Extensive History of Tigard